Post

#|WhenThisIsAllOver | Nicholas Falk | URBED

13 May 2020

Post-covid, the battle will be to create a healthier city, says Dr Nicholas Falk of URBED, and the key areas will be London's suburban town centres.

We are facing another war, but this time the enemy is largely invisible. As cities like London seek to recover from an epidemic that has left the streets in a state of suspended animation, it will be impossible to return to business as usual. Our former enemy Germany has suffered a fifth the death rate, and its towns and economy are in a much stronger position. It is at the heart of Europe, not the edge of nowhere! When industries closed, as they did in Eastern Germany after reunification or in the old coal and iron belt of the Ruhrgebiet, the sites were returned to woods and lakes. Trams and cycle paths kept car use down. In contrast the UK already has over-invested in shopping malls, and its urban roads are congested and unsafe.

After the First World War, a policy of ‘Homes for Heroes’ led to endless suburbs of semi-detached houses, which led to the imposition of tight green belts. But Garden City principles and extensions to the London Underground drew people out to expanding towns like Ruislip, which are still very pleasant places for families. After the Second World War, London’s bombed East End was rebuilt through Comprehensive Development Areas. Councils such as Southwark and Lambeth compulsorily acquired land for rebuilding. Outside London New Towns were built by development corporations to provide jobs and homes in healthier surrounding. However continued centralisation has robbed communities of the resources and capacity to keep neighbourhoods healthy.

Now that many ‘inner city’ areas have been gentrified, and people from overseas have taken over the old shops, the ‘front line’ has shifted to the outer suburbs. Before ‘lockdown’ return visits to centres that URBED had once advised such as Peckham and Lewisham suggested they were finding niche markets, and attracting young people to fill any gaps. Uxbridge too looked much healthier, thanks to an influx of major employers round the town centre. The surrounding environment seemed green, pleasant, and quite special.

But most High Streets in London have no room for bypasses, and orbital traffic normally thunders through. It is the pollution from car tyres as well as exhausts that research suggests could be the main killer, as well as contributing to global warming. Their residents look depressed. So how could we use recovery to tackle the ‘giant’ challenges’ of inequality, poor health, unaffordable housing, and a general lack of hope that afflicts many people in the centres of the poorer suburbs of places such as Brent, Hackney, and Newham that have fared worst from the epidemic? We should take inspiration from the Beveridge Report of 1942, as well as the Abercrombie Plan again produced before the end of the last war.

Following research for Ken Livingstone entitled ‘ A City of Villages, URBED was commissioned to produce a ‘toolkit’ for making them more sustainable. The proposal, based on applying proven best practice, are still applicable, but were never put into effect due to lack of capacity. With a new Mayor ReShaping London, Jonathan Manns and I on behalf of the London Society used a case study of outer West London to show what could be done if only under-used land was mobilised. Proposals included new housing along the canal on storage yards close to stations, and a new Garden City on Northolt Airport, which is just off the A40 and has three stations on the London Underground lines, along with extensive greening. Again this was all seen as ‘too difficult’, and reliance was placed on private developers.

Our research study for the Deputy London Mayor on mobilising land with Dentons and Gerald Eve proposed Land Assembly Zones and other changes, modelled on what had worked in the past and in Continental Cities. Subsequently I showed how the uplift in land values from development could be shared, and used to help fund local infrastructure, as is common in German and Dutch cities. With property values falling, could now be the time to mount a battle plan, and set up task forces to bring our High Streets back to life?

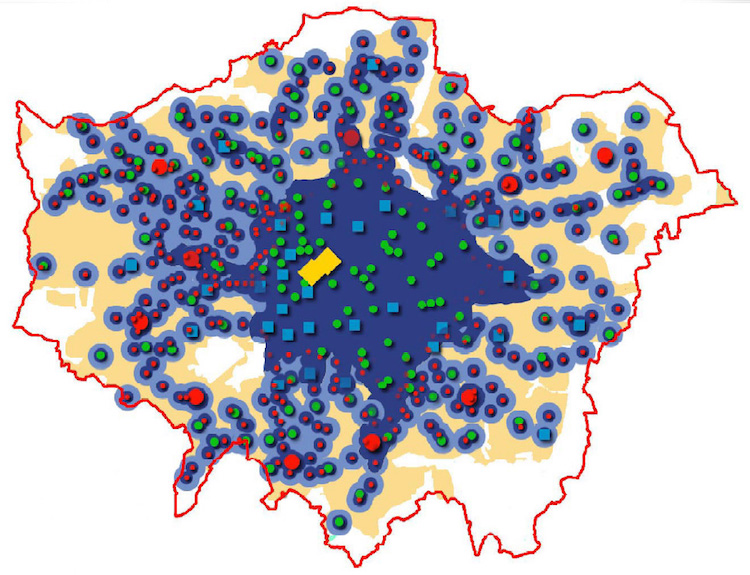

Having spent over 40 years working as a consultant and researcher on urban regeneration, and having led study tours to many places that could serve as models, I believe that unless we apply similar approaches to planning, development and public finance as in the rest of Northern Europe we will fail to restart our economy. We will also lose precious assets as buildings rot or go up in flames. So the London Society, and others concerned with urban quality, should not just be recording history but helping to rewrite it. Instead of radar, we have the power of GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and modelling to identify and screen opportunities. We have much better communications, now that internet based meetings are common place, and information can be quickly shared. We could start with the network of green and blueways that characterise many of London’s suburbs, and use them, and under-used railway lines, to bring dead places back to life.

Dr Nicholas Falk BA MBA is the founder of URBED, and executive director of The URBED Trust, www.urbedtrust.com

WhenThisIsAllOver is the London Society's debate about what the post-virus, post-lockdown world will and should look like. Contributions so far include:

- Chris Williamson | Weston Williamson + Partners | Change is needed

- Clare Richards | ft'work | Local is central

- James Raynor | Grosvenor Britain and Ireland | We need system change

- Freddy Mardlin | London’s Outside Space

- Andrew Beharrell | Pollard Thomas Edwards | Reevaluation

- Amy Warner | Appreciate More

- Mike Stiff | Stiff + Trevillion

- Lord Toby Harris | London will need fresh purpose

- Matt Brown | How should we commemorate the heroes?

- Peter Murray in conversation with Robert Elms

- Prof. Samer Bagaeen | Create a resilient economy

- Neil Bennett | Farrells | High Streets must Act or Die

- Buckley Gray Yeoman | How can design respond?

- Alistair Barr | Bring production back to the West End

- David Morley | There's only one Way

- Chris Williamson | Getting back to work

- Nicholas Falk | URBED | The suburban battle grounds

- Roland Karthaus | Matter Architecture | Institutional architecture in a time of crisis

- Jonathan Manns | Rockwell Property | Planning for #WhenThisIsAllOver

- Daniel Moylan | We need to stop telling people what to do

- Dr Meredith Whitten | We need a green infrastructure

Please give your views in the comments below, or by emailing blog@londonsociety.org.uk