Post

#WhenThisIsAllOver | David Morley

12 May 2020

We're asking for your thoughts on what will change and what should change in London in the post-covid world.

Here, David Morley of David Morley Architects says that there's a simple and immediate change that can aid social distancing.

Just after the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, David Morley Architects held a seminar about the role of temporary structures in urban design. We were joined by Peter Bishop, Morwenna Wilson from Argent, Richard Hannay from LUC and Neil Smith from Max Fordham. There was an emerging consensus that temporary interventions provide valuable opportunities in city master-planning to try things out, without too much investment, before committing to the costs of long term infrastructure. Our experiences over the last few months, with huge sacrifices for some, have forced on us some temporary interventions from which we can also learn valuable lessons about how our cities will work better when ‘this’ is all over.

If ‘this’ means the threat of a deadly pandemic it won’t be over until we find suitable vaccines. It seems this may be some way off. In the meantime, we have shown how we can do more with less - burning less fossil fuels, working effectively with much less workspace, spending less time commuting. We have seen how government can act with a sense of real urgency and bring in radical change to our environment. Let’s hope these lessons can also be applied to our other emergency – climate change.

However, if ‘this’ means the lock-down, then there are some immediate challenges to address when ‘this’ is all over. Whilst we might be well prepared for new ways of using the workplace and we are excited about adapting homes to become great places to live and work, we have not solved how public transport can be compatible with the emerging requirements for social distancing. The easy answer is to say walk more or get on your bike. But if we create more space for bikes, by reducing space for cars, are London’s pavements capable of both accommodating more people and enabling adequate social distancing? Keeping the two metre rule will be almost impossible, but a real difference could be made if we were to introduce one-way pavements. Supermarkets have already introduced one-way circulation systems and there is talk of one-way routes becoming part of office planning for those who choose to return to the traditional workplace. It’s already part of sports stadia design - even the Pavilion at Lord’s Ground has a one way system where the exit to the WCs is marked ‘out’ and the entrance ‘not out’!

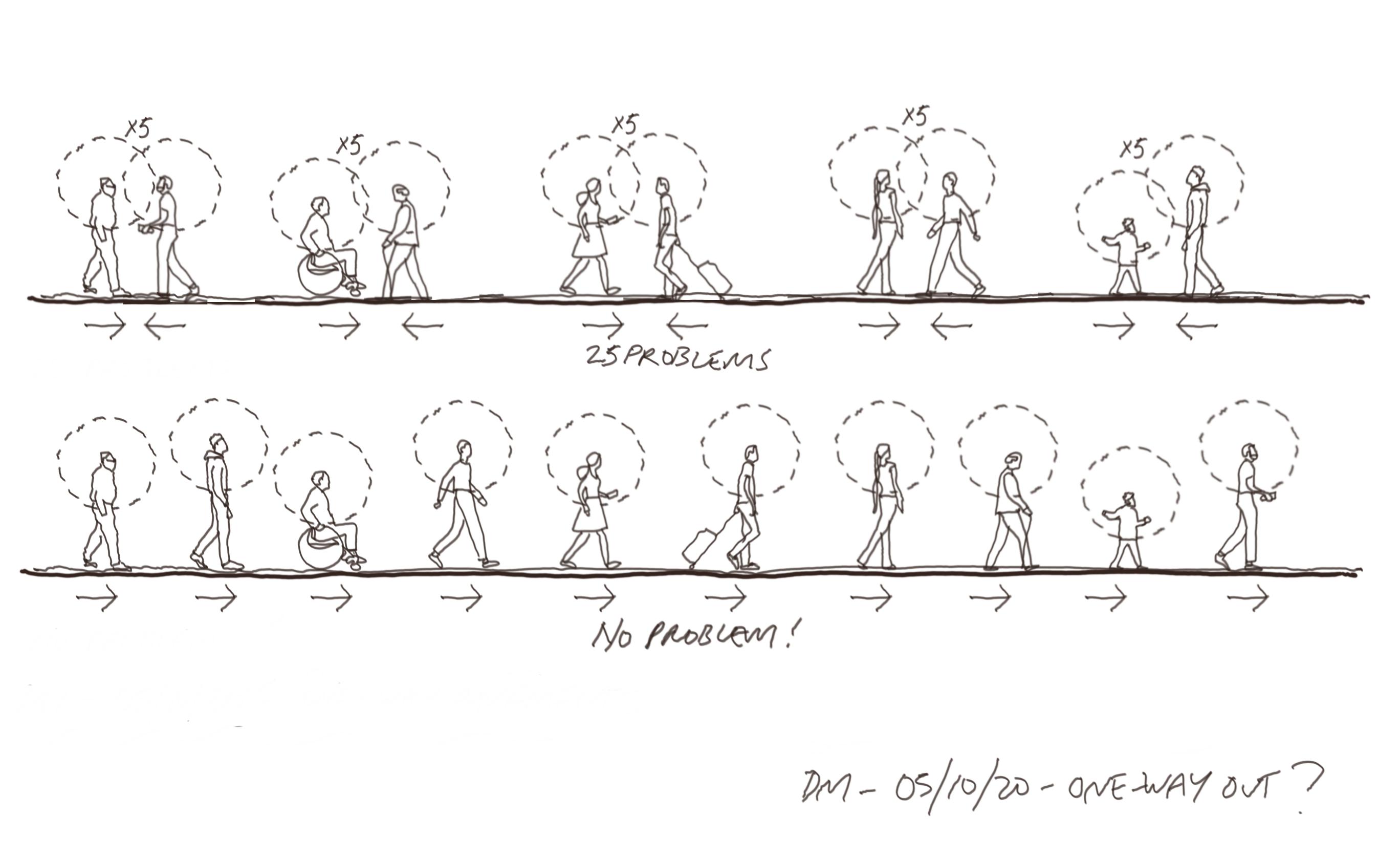

If there are ten people on a path, five walking in each direction, there will be 25 instances of people passing close. However, if all ten walked in the same direction at similar speed, the figure drops to zero. So why not adopt a similar system on our pavements? One-way systems were a curse for cyclists. By making journeys longer there was a valid argument that one-way streets discouraged cycling. If you are moving under your own man-power, the extra metres make all the difference. But the same objection need not apply to pedestrians - most London streets already have two pavements and allocating a one way flow to each should have minimal impact on overall travel distance.

It is not unprecedented to ask people to walk on one side of the road or the other – it’s part of the countryside code to ensure walkers face oncoming traffic. We naturally adapt to up and down escalators. One way corridors were introduced in some schools, before this pandemic, to improve behaviour. One of the world’s greatest treks, the Milford Track in New Zealand can be walked in one direction only, precisely to enable better social distancing.

Regardless of the need for social distancing, I can imagine places like Oxford Street and Waterloo Station becoming much more enjoyable promenades if one didn’t have to jostle with people from opposing directions. I would advocate walking on the right, to face oncoming cycles and buses. It needn’t apply to all pavements, but even on uncontrolled routes we could begin to adopt a natural habit of always passing to the right – rather like boats steaming in an estuary.

To implement this concept on London’s busiest pavements could be relatively inexpensive. Indeed it could be trialled as a temporary measure to see how well it works. As far as I can see, it’s not part of the London Mayor’s emerging plans for making our streets work better – maybe it should be?

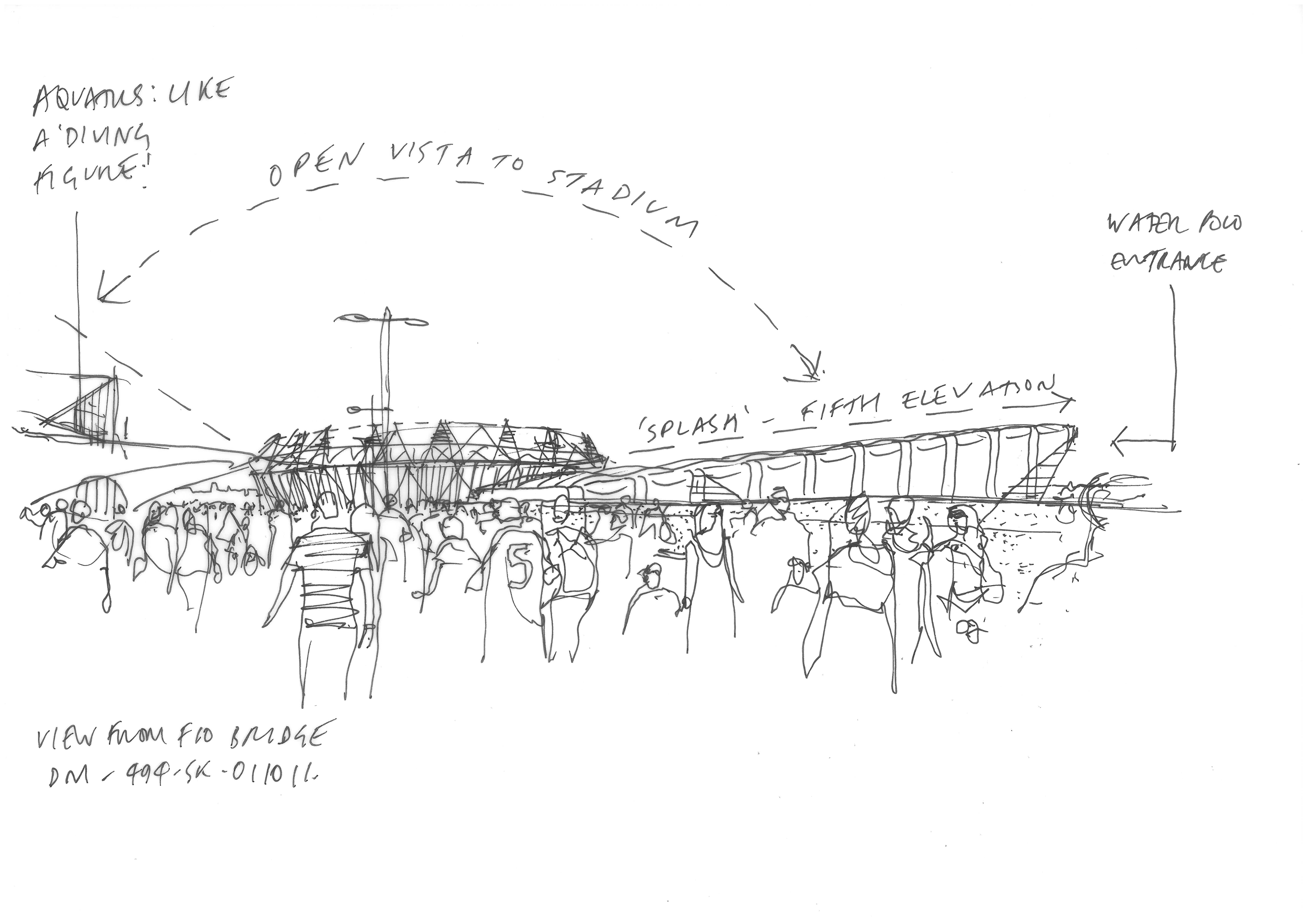

Having founded David Morley Architects in 1987, after 13 years working with Norman Foster, David has brought together a team that have designed 500 projects winning over 100 awards. These include pioneering healthcare projects, 15 projects at Lord’s Ground, three projects at the University of Oxford, the London 2012 Water Polo Venue, five projects for the Royal Parks and three projects at London’s King’s Cross. David is an honorary scholar of King’s College Cambridge and published his first book ‘Five by 5’ in 2012. He judges RIBA Competitions and the Wood Awards.

WhenThisIsAllOver is the London Society's debate about what the post-virus, post-lockdown world will and should look like. Contributions so far include:

- Chris Williamson | Weston Williamson + Partners | Change is needed

- Clare Richards | ft'work | Local is central

- James Raynor | Grosvenor Britain and Ireland | We need system change

- Freddy Mardlin | London’s Outside Space

- Andrew Beharrell | Pollard Thomas Edwards | Reevaluation

- Amy Warner | Appreciate More

- Mike Stiff | Stiff + Trevillion

- Lord Toby Harris | London will need fresh purpose

- Matt Brown | How should we commemorate the heroes?

- Peter Murray in conversation with Robert Elms

- Prof. Samer Bagaeen | Create a resilient economy

- Neil Bennett | Farrells | High Streets must Act or Die

- Buckley Gray Yeoman | How can design respond?

- Alistair Barr | Bring production back to the West End

- David Morley | There's only one Way

- Chris Williamson | Getting back to work

- Nicholas Falk | URBED | The suburban battle grounds

- Roland Karthaus | Matter Architecture | Institutional architecture in a time of crisis

- Jonathan Manns | Rockwell Property | Planning for #WhenThisIsAllOver

- Daniel Moylan | We need to stop telling people what to do

- Dr Meredith Whitten | We need a green infrastructure

Please give your views in the comments below, or by emailing blog@londonsociety.org.uk