Post

London's Housing | Semi-Heaven

31 May 2022

This is the latest in a series of short essays about where Londoners live, written by Andrew Beharrell, Senior Advisor, Pollard Thomas Edwards. (You can read his 'Mansions for the Many' on mansion blocks here) He is interested in the ordinary places - the most common types of home and neighbourhood, which have driven the capital’s historic expansion - not the architectural award-winners. What makes these places enduringly popular, and what can we learn from them when considering how to revive existing neighbourhoods and create new ones today? Drawing on personal memories of the homes in which he has lived in or visited often, and encourages readers to share their own experiences and insights.

Andrew will talk about London's 'semi-detached suburbs' in this London Society talk on 21 July. More details here.

In 1993 I moved with my young family to a semi-detached house in Hampstead Garden Suburb. We stayed for 16 years and moved only because of an opportunity to build our own place nearby. Like many of our neighbours, we were only the third generation of owners of our 1935 house: we know couples who moved in when they first had children and plan stay until they are carried out. The houses are large enough, but not too large, and they are endlessly adaptable. One family we know has remodelled three times: to accommodate three young children, two careers and a nanny; to provide semi-privacy for teenagers; and now to suit semi-retirement for music-loving bibliophile empty-nesters.

When we moved in, our house was impeccably clean and relentlessly beige. Little had changed since the 1930s, and we gently lifted it into the modern age, keeping the sensible room layout, lovingly restoring the draughty Crittall windows and the cream and black bathroom tiles, stocking the teak veneered wardrobes, with their original trouser press, cufflink drawer and tie rack. Far away in Northumberland on a freezing New Year’s Eve, soon after completing our restoration, we received a call from our neighbours to say that our house had suffered a catastrophic plumbing leak. The fire brigade had to break in to shut off the water, which had been cascading under pressure from a broken pipe in the roof and had seeped through the party wall. Teapots inside kitchen cupboards were full to the brim, such was the downpour. The point of this story is that the construction was so robust that the house dried out with relatively little damage, helped by the suspended ground floor and raised threshold, not permitted today: the water just poured through and out into the street.

HGS is clearly a rather privileged suburb, rigorously conserved in its original state by a Trust, which does not hesitate to serve enforcement notices on illicit installers of plastic windows, or to name and shame householders who erect satellite dishes. One of its greatest achievements, in sad contrast to most London suburbs, is the preservation of front gardens from being concreted over for parking.

Devon Rise inspired me to write a homage to the suburban front garden called Privet Lives, celebrating the many positive impacts of the humble hedge: on the environment and ecology; on air quality and privacy; on jobs for gardeners and exercise for householders [1] . Above all, front gardens and front gardening provide opportunities for casual social interaction – and during the pandemic they have come into their own for socially distanced doorstep encounters. Book-clubbing, hedge-trimming, car-washing and produce-swapping – these cliches of the suburban good life are precious everyday activities which create a context for a sociable society.

Reflecting on this period in my life made me wonder why this excellent housing type has been so long neglected (if not derided) by architects and planners, and to reflect on the future of London’s suburbs under threat from active densification and casual neglect.

Origins and Perception

London’s biggest building boom took place in the 1920s and ‘30s with massive expansion of the suburbs around new commuter rail and underground links. The great architectural legacy of Metroland is the semi-detached house. There are around 541,000 semis in the Outer London Boroughs. The inter-war semi is probably the most under-appreciated of London’s major housing typologies. Although often derided by the professions and the press, it is enduringly popular among residents of London’s suburbs, and accounts for over 10% of our housing stock. The semi is endlessly adaptable to changing demands and circumstances.

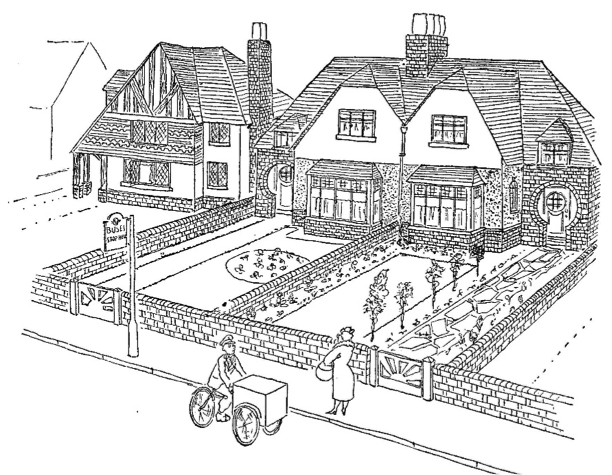

The suburban semi-detached house was pioneered by distinguished architects and planners of the Arts and Crafts and Garden City movements, and it was popularised by the developers of what Osbert Lancaster famously dubbed ‘Bypass Variegated’ [2]. They all extoll the merits of a house with its own front door, and gardens front and rear. Pairing offers the appearance and status of a ‘villa’ and the practical benefits of a garden-passage and side-windows – at a lower development cost and higher site density than a detached house.

‘Metroland’ is now used, with growing affection displacing scorn, to describe the inter-war outer London suburbs. It was originally coined (as Metro-Land) by the marketing people for the Metropolitan Railway as it pushed out into North-West London and beyond.

The semi-detached house is by no means the only typology found in the suburbs, but it is the predominant one, and, for most of us, it captures the character and image of Metroland, in both innocent times, and times of neglect and degradation. Nor is the inter-war semi the first application of this typology - its origins lie in Victorian paired villas, model cottages for agricultural workers and the artful pairings of Richard Norman Shaw at Bedford Park and Parker and Unwin at Letchworth, and their many collaborators – but the builders of London’s inter-war suburbs rolled it out as popular housing for aspiring people on modest incomes.

While the suburbs provided an accessible arcadia for their residents, they became a lightning conductor for the snobbery of higher-minded people – some of whom came from the places they so despised. In The Intellectuals and the Masses, John Carey devotes a whole chapter to ‘The Suburbs and the Clerks’ [3]. Many pre- and post-war writers describe the soul-destroying conformity and ugliness of the suburbs. Here is George Orwell in Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936) on ‘’the futility, the bloodiness, the deathliness of modern life’’ and in Coming Up for Air (1939) on ‘’semi-detached torture chambers where the poor little five-to-ten pound a-weekers quake and shiver’’ [4]. Osbert Lancaster wrote: ‘’It is sad to reflect that so much ingenuity should have been wasted on streets and estates which will inevitably become the slums of the future. That is, if a fearful and more sudden fate does not obliterate them prematurely: an eventuality that does much to reconcile one to the prospect of aerial bombardment.’’

Disappearing from view

The semi and the suburbs did not get much of a look in during my architectural education in the early 1980s, which elevated the inner city as an aspiring architect’s proper habitat. The closest we came was a coach tour of Milton Keynes, in which the greatest respect was reserved, not for its many suburban culs-de-sac, but for the heroic reinvention of the classical terrace at Netherfield (1972), with its emphasis on total control and uniformity [5]. This grand vision has alas been subverted by residents’ unstoppable urge to customise their homes.

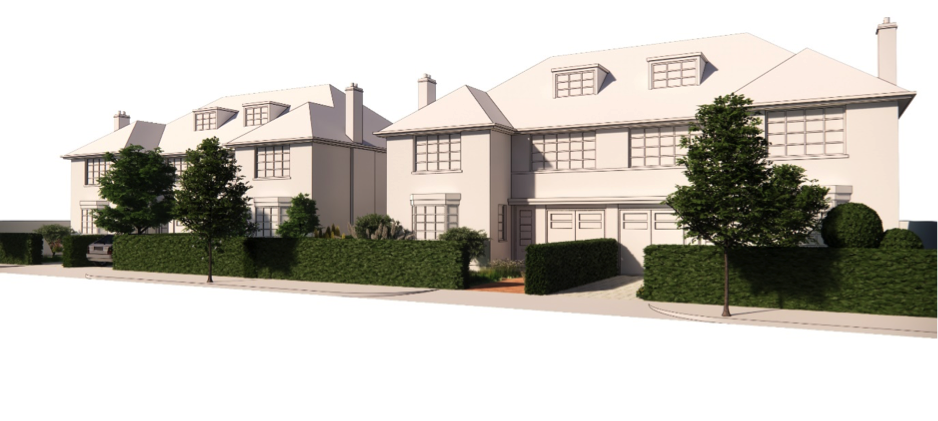

I think that architects started to take a more positive view of London’s outer boroughs when, priced out of Camden and Islington, we began the great migration to Enfield and Waltham Forest. Today there is some excellent new housing which shows a real understanding and affection for the suburbs: for example, this inspired reinvention of the asymmetrical paired villa by Sergison Bates.

Gateway to heaven

The side-passage and the party fence are the defining characteristics of the semi-detached house. The relationship between ‘adjoining’ owners, whose two conjoined dwellings form a pair, is subtly different from the relationship between ‘adjacent’ owners, separated by that mystical space the side-passage. The competitive jousting of adjoining owners was satirised in the Bonzo Dog Band’s 1968 song My Pink Half of the Drainpipe (I think I’ll paint it blue): they may be best of friends or lifetime enemies, but they have to cooperate to preserve the integrity of the ‘unit’. Adjacent owners are physically separate, but the side passage is an intimate shared space, with endless opportunity for social connection or conflict.

There are three basic arrangements, which are repeated all over London: paired narrow side passages separated by a fence or hedge - although sometimes removed by agreement or neglect; wider shared passage, leading to a pair of garages at the rear – sized for an Austin Seven rather than a modern SUV; wide private side passage, accommodating a car space or garage. These variations, coupled with the original affluence of the neighbourhood generate several variations in plot width from a minimum of around 7.0m to a generous 12m.

The side passage served several important practical purposes: access to the garden for the import of manure and the extraction of produce, which reaches its zenith in the Dig for Victory campaign during WW2; access to the kitchen side-door in a period when trades people were not welcome at the front door and middle-class households might have a daily help or even a live-in maid; access for coal supplies and extraction of ash, together with household refuse, which was a tiny fraction of what we chuck out today. The semi-detached arrangement also enabled side-windows, especially to stair landings and WCs, and location of boiler flues and pipework away from the main façade.

Beyond these practical considerations, the side passage is a gateway to the private heaven of the back garden and the secret world of shed-land. In low value areas this has taken on undesirable associations with illegal sub-standard housing for disadvantaged people, including low-wage migrant workers: ‘beds-in-sheds’. Elsewhere, Londoners have a more romantic view of the garden shed as a haven for hobbies, a mini-warehouse for storing stuff and a micro-business HQ. In the iconic 1970’s TV sitcom The Good Life Tom and Barbara Good create a completely self-sufficient small-holding in their Surbiton back garden (actually filmed in a pair of real semis in Northwood). The side passage sees a traffic of livestock and produce, and the Goods even generate power from manure. With their longing for a simpler healthier life, they are the apostles for today’s anti-globalisation and Slow Food movements.

When PTE designed a street of new family houses in Cricklewood five years ago we started with a homage to the semi, but then persuaded ourselves that the space occupied by the side passage was better used to expand the ground floor accommodation. We reasoned that today people want small low-maintenance gardens more suited to barbecuing pigs than raising them. I now wonder whether our obituary to the side passage was premature, especially given the importance gardens have taken on during the pandemic – for those lucky enough to have one. How many flat-packed home-offices have been threaded into suburban back gardens to support the new normal of working from home?

Self-help for the Suburbs

This is an opportune moment to reconsider the future of those expansive low-rise suburbs which lie between the ‘growth areas’ and ‘opportunity zones’, and to reappraise their distinctive contribution to domestic life and the everyday architecture of the semi-detached house.

Policy Exchange’s recent report Strong Suburbs [6] considers the prospects for gradual growth and change, based on homeowners getting together to vote for increasing density on their streets and making some money in the process.

Similar ideas were trailed in a 2015 joint submission to the NLA from HTA Design and Pollard Thomas Edwards: Transforming the Suburbs: Supurbia and Semi-Permissive [7].

This report shows how incremental and small-scale urban intensification of suburban London can increase housing choice and supply, promote economic activity, improve local service provision and reduce car dependence – whilst improving quality of life, including green open space. Doubling the density of just 10% of the outer London Boroughs could create one million new homes.

Pollard Thomas Edwards has recently carried out a detailed study for a south London borough applying the spatial ideas behind semi-permissive to incremental intensification and upgrading of their own stock of inter-war suburban housing.

Suburbs under Pressure

Meanwhile the suburbs are increasingly under pressure to accommodate dense new housing developments. As inner London runs out of development land and politicians of all flavours lack the courage for serious review of the Green Belt, the obligation to deliver new housing in volume falls on the outer boroughs, which cover nearly 80% of London’s land area. It falls especially on those suburban town centres, which enjoy the benefit – or suffer the curse – of good public transport connections. If you visit North Acton today you will see a vision of high-rise Gotham City erupting from a sea of semis, in anticipation of the eventual opening of Crossrail. While the logic of concentrating higher density development on well-connected town centres is hard to fault, the reality is a world of housing units and dormitories – will they mature into homes and neighbourhoods? And, if London’s allure and property values falter in a post-Brexit and post-pandemic world, will people choose to live in the newly dense suburban centres, or will these places become a focus for those who depend on subsidised housing and have little or no choice? Will the new places we are creating today have the longevity of the low-rise suburbs over which they loom?

Suburban evolution

Let’s slow down the superdense redevelopment of suburban town centres while we assess the long-term impacts and figure out how to do it better. Let’s help London’s outer suburbs find their proper place in the 21st Century by appreciating their underlying qualities and encouraging incremental transformation, rather than the current choice between neglect or drastic change. Let’s apply innovative thinking (like Strong Suburbs and Supurbia) and new technologies (like e-bikes, Passivhaus and its retrofit equivalent Enerphit) to make them more sustainable.

Andrew will talk about London's 'semi-detached suburbs' in this London Society talk on 21 July. More details here.

- [1] Privet Lives by Andrew Beharrell for Future of London https://www.pollardthomasedwards.co.uk/journal/privet-lives-placemaking-in-suburbia/

- [2] Pillar to Post – English Architecture without Tears by Osbert Lancaster (1938) – republished by Pimpernel Press Limited 2015

- [3] Quoted in The Intellectuals and the Masses, Pride and Prejudice among the Literary Intelligentsia 1880 – 1939 (Faber and Faber 1992) John Carey devotes a whole chapter to The Suburbs and the Clerks.

- [4] Quoted in Ged Pope’s All the Tiny Moments Blazing – A Literary Guide to Suburban London (Reaktion Books) - recently presented to the London Society – which contains many excerpts from pre- and post-war writers describing the soul-destroying conformity and ugliness of the suburbs.

- [5] Netherfield was a development of 1.043 rental homes by Jeremy Dixon, Ed Jones, Chris Cross and Mike Gold for the Milton Keynes Development Corporation.

- [6] Strong Suburbs – enabling streets to control their own development by Policy Exchange 2021.

- [7] Transforming the Suburbs: Supurbia and Semi-Permissive by HTA Design and Pollard Thomas Edwards, with support from Savills and Nathaniel Lichfield and Partners http://www.supurbia.info/.