Post

Andrew Beharrell: Mansions for the Many I

12 Feb 2021

Andrew Beharrell is Senior Adviser at the architects' Pollard Thomas Edwards. A former director and senior partner, Andrew Beharrell has designed and delivered many award-winning projects throughout his 30-plus years with the practice. Now, as one of two senior advisors, he lends his expertise to PTE’s research and development group Knowledge Hub, maintaining and improving design standards across the practice.

In this two part article, he examines that great London building type, the Mansion Block, looking at its history and evolution, at the flexibility it still affords, and at how his life and career have been influenced by this typology. You can download the whole piece here as a PDF.

Mansions for the Many

The mansion block is back in fashion as an inspiration for today’s housing. Phrases like ‘modern mansion block’ and ‘new London vernacular’ aim to confer a comforting connection with London’s domestic heritage, even when proposals are bafflingly remote from the Victorian and Edwardian originals: I recently saw a 12-storey corridor-access slab described as a contemporary mansion block.

The precedent is better understood by the government-appointed Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission. In Living with Beauty (2020) [i] they promote the mansion block as part of the way to deliver ‘gentle density’ and roll back the tide of high-rise. They illustrate their report with one of my favourite examples, The Pryors on Hampstead Heath.

We have previously calculated that the original inner London mansion blocks often achieved around 200 homes per hectare, which qualifies as ‘superdensity’ [ii] and is in the upper range of the GLA’s recently retired density matrix.

The fact that we can use such the word ‘mansion’ today without blushing, is perhaps evidence of the popularity and durability of the originals, which were generally aimed at the more prosperous end of society – in contrast to ‘charitable dwellings’ for the poor, which adopted a distinctive architectural form and language, including deck-access tenements.

There is no commonly agreed technical definition of ‘mansion block’ or ‘mansion flat’. Estate agents like the status conferred by ‘mansion’ and Wikipedia follows suit with ‘apartments designed for the appearance of grandeur’. One of the earliest examples is Richard Norman Shaw’s Albert Hall Mansions of 1879. Purpose-built flats for the wealthier classes were such a rarity in London, that the architect travelled to Paris for inspiration [iii]. Elaborately articulated and decorated street frontages with grand entrances helped to distance the new typology from ‘model dwellings’ for the working classes, which charities such as Peabody started delivering in the 1860’s.

My definition of a mansion block might run something like this: mid-rise apartment block, typically four to eight storeys, with 2-8 flats per level, usually arranged around a compact stair core. Adjoining blocks are often grouped to create a continuous street frontage, each having a prominent front door. This definition distances the mansion block from other common contemporary typologies: corridor access, deck or gallery access and point block.

Mansion Memoir

My enthusiasm for the mansion block began in childhood and was reignited by recent walks in lockdown London. My work, and that of colleagues at Pollard Thomas Edwards (PTE), has long been influenced by the typology. We have built many variations over the past 40 years and, I admit, often used the phrase ‘modern mansion block’. These projects have provided homes for all sorts of people, from wealthy penthouse power-couples to disadvantaged families. In the late 90’s we did a row of mansion blocks overlooking Victoria Park, and I remember that one local family occupied three separate flats: the parents were social renters, one adult daughter bought under a shared ownership scheme and one was able to buy outright. These were truly mansions for the many.

Here are some mansion block milestones on my personal journey, which also chart the changing character of London and show how the typology has evolved from exclusive to inclusive.

Sloane Gate Mansions

As a child I would be taken by train up to London to visit my grandmother at Sloane Gate Mansions in D’Oyley Street, round the corner from the Cadogan Hall. My grandmother Victoria lived with her sister Rita on the first floor: the bay-windowed sitting room and their two bedrooms overlooked the street, and the bedrooms were wedge-shaped to turn the corner. The hall was large enough to contain a mahogany dining table, and lunch was wheeled here on a small trolley from the servants’ wing at the back. There were no servants and not much money. I was already fascinated by people’s homes and intrigued by the complexity of my grandmother’s flat with its original scullery, kitchen and sewing room.

My grandmother was born in 1898 in South Africa and sent to London on the White Star Line in 1920 to find a suitable husband. She married a former cavalry officer, who founded the Nairobi Coffee Company. My grandfather was a great salesman and a pioneer of today’s ubiquitous coffee culture, obtaining wholesale orders from West End hotels. He died in 1957, and my grandmother lived as a widow for 33 years. She loved London and seldom ventured far from Sloane Gate Mansions: the world came to her, with a constant stream of visitors from South Africa and elsewhere. Peter Jones supplied all of life’s necessities and Harrod’s Food Hall the occasional treat.

London as an international hub and cultural melting pot is nothing new. I remember descending with Rita in the creaking lift cage, and the concertina door being held open for her by a polite young man in floral shirt, zebra-striped jeans and long boots - identified by my awe-struck brother as Mitch Mitchell, drummer to the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

My grandparents never owned property. It was more normal to rent in those days. From overheard conversations among the grown-ups I gathered my grandmother’s rent was controlled and modest, and that she ignored all inducements to vacate.

Victoria and Rita lived in a time capsule. The furniture and decoration were mostly from the 1920’s, with some earlier antiques. As they got older and money became tighter, the better pieces gradually thinned out: Victoria would mention casually that a nice young man from Sotheby’s had been to visit. There was a sort of shrine with military portraits of my grandfather and his brother, who won a posthumous Victoria Cross in the final German assault on the Somme, with their medals displayed in a glass cabinet. Rita had designed lampshades and curtains for Fortnum & Mason in the twenties: there were lots of tassels. I was aware of the contrast between the front rooms, and the back rooms, which featured linoleum and ‘utility furniture’, which was mass-produced in plywood after WW2: I still have several pieces.

Gardnor Mansions

After my grandmother died, the few remaining antiques crossed London from Sloane Gate Mansions to Gardnor Mansions on Church Row in Hampstead, joining the treasures which my uncle and aunt had assembled in a lifetime working in the Near East. They bought the flat in 1963 and rented it out for most of the 30 years they were based in Cyprus, Jordan, Beirut, and Istanbul. They are still there in their nineties.

It is a typical mansion block plan, with a formal front room, flooded with light from its south-facing bay window, and then a long tail of back rooms, dimly lit from a small internal lightwell. A long corridor is lined with bookshelves and pictures: we tend to regard circulation today as a waste of space, but mansion flats demonstrate that it can make a positive contribution to domestic character and utility. My uncle’s flat, like my grandmother’s, was built with a miniature service wing at the back, and this converted seamlessly into a self-contained micro-flat for a lodger.

Gardnor Mansions consists of 20 flats in two adjoining blocks built in 1898 and slotted into one of Hampstead’s oldest streets. They are taller than the adjoining early Georgian houses, and the Queen Anne Revival orange brickwork may have seemed a little brash when new, but time has harmonised the mansions with their neighbours. There are no lifts to serve the five storeys plus semi-basement, which even today would be costly for such small blocks, but this enables just two flats per landing, with every flat enjoying the full depth of the building.

The small size of the blocks, and generous design of the stair and landings, makes Gardnor Mansions a very neighbourly place: everyone seems to know everyone else, despite nearly every household being from a different country of origin – or perhaps the global mix actually promotes interest in and courtesy towards neighbours. During the pandemic, several people in the block are looking out for my elderly relatives and providing practical help with shopping. The lobby name boards, identifying each resident and whether they are in or out, are a symbol of trust and openness: should we reintroduce them to modern apartment blocks?

Tower and York Houses

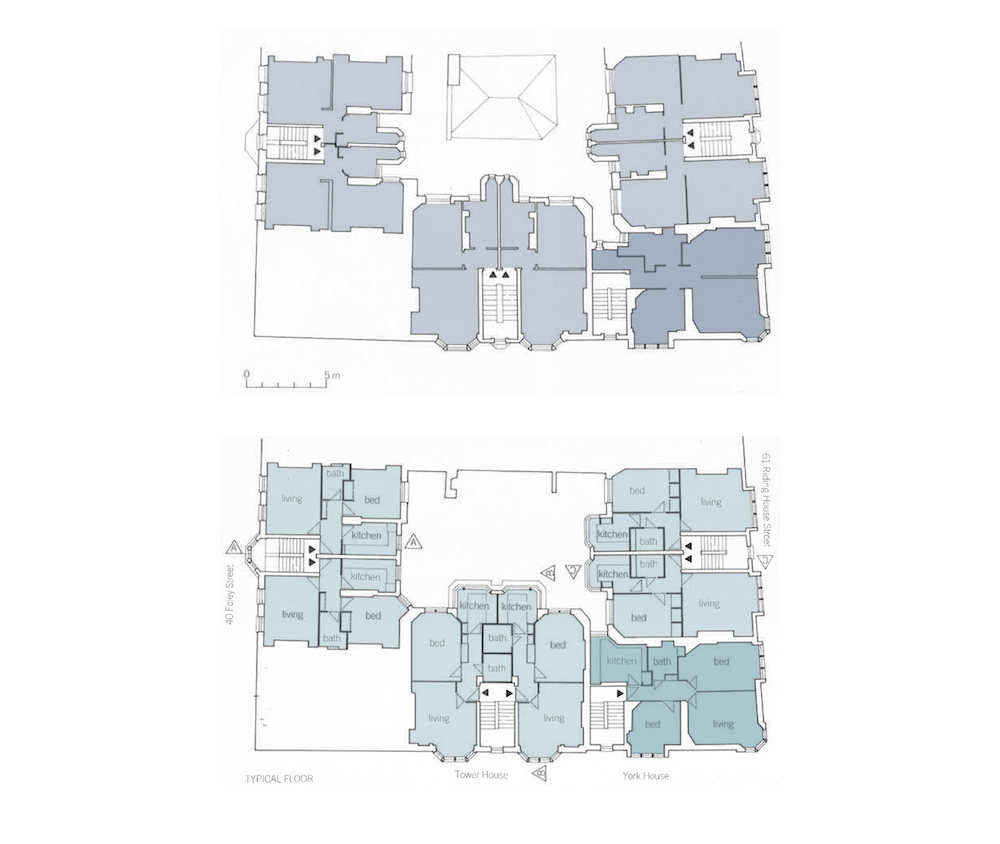

My first major job as a newly qualified project architect in 1985 was the remodelling of a pair of mansion blocks in Candover Street and Riding House Street on the Howard de Walden estate.

Tower and York Houses were designed by Herbert Fuller-Clark in 1903 to house respectable clerks of modest means [iv]. The flats were self-contained, but tiny, with a sitting room at the front, bedroom, and small kitchen / pantry at the back. Overall size was 38 sqm (compared with today’s national minimum of 50 sqm): these were the micro-flats of their day, a century before Pocket Living. They had a WC but no bathroom: baths were taken in a tub in the kitchen. All the original ogival mouldings, doors and built-in cupboards survived. Again, there was no lift to serve the two flats per floor over five storeys.

No expense was spared on the exterior, which features bay windows and stair towers with fine Queen Anne Revival proportions and red brickwork decorated with white rendered banding. The most striking feature is the green and gold mosaic advertisement for T J Boulting & Sons, Sanitary and Hot Water Engineers, which was also the developer. It is hard to image today a business having the sense of permanence to enshrine its marketing in mosaic or a planning authority agreeing to make an adverting hoarding the main feature of an apartment block.

Our task was to retain all the key features of these Grade 2 Listed buildings – or replace them with replicas where deterioration or fire regulations required – while updating for modern lifestyles. We took down the rear extensions, which backed into a deep lightwell, and replaced them with new bathrooms and kitchens. We also extended the stairwells up to access new shared roof gardens.

The blocks were owned by Community Housing Association (later absorbed into the giant One Housing). This was my first experience of resident engagement, and I was surprised that the tenants were not the downtrodden poor, but middle-class professionals: I remember doing bespoke interior designs for a journalist. As well as serving disadvantaged people, housing associations at that time provided rented homes for those on moderate incomes who could not afford to buy in London (and certainly not in Westminster) – what we now call the ‘missing middle’.

The procurement and contract administration were also rather different from today. The contractor was a family firm with directly employed craftspeople, who knew how to build without being closely instructed. They tolerated being ‘supervised’ by an inexperienced young architect and helpfully corrected my more foolish instructions. The final account was agreed over a pub lunch, and the Housing Corporation accepted over-spend up to 15% of their already generous 100% grant funding.

You can read Part II of Andrew's post here. Or download the whole piece as a PDF here.

Footnotes

[i] Living with beauty: report of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission

[ii] Superdensity

[iii] Richard Norman Shaw by Andrew Saint (published by Yale University Press 1977)

[iv] Robert Thorne in The Architects’ Journal 1988 Number 5 Volume 189