Post

Why we need well-designed ‘dense cities’ not overcrowded buildings

23 Mar 2021

Félicie Krikler is a director at Assael Architecture, and specialises in residential-led urban regeneration. She leads several research initiatives in the practice, including build to rent, ‘later living’ design and high street renewal.

On 25th of February, I took part in a London Society panel discussion chaired by Kyle Buchanan from Archio, and shared my thoughts on how the changing nature of our homes’ usage in 2020 has highlighted stark inequalities in housing throughout the UK. The discussion focused on the implications of density in cities on people’s health and wellbeing, and the inequalities of housing, not a new reality, but one on which Covid-19 has shone an intense spotlight.

The short presentations sparked many remarks and questions, which couldn’t all be answered on the evening, and therefore I have tried to answer some of them below.

A fundamental question at the heart of the debate was whether an alternative to the word ‘density’ should be used. Housing density is essentially a measure of the number of people living on a given area of land. The measures used in documents across the spectrum of land use planning systems vary but in the residential context generally come down to three main categories: Numbers - including numbers of dwellings, numbers of rooms (habitable rooms, bedrooms, bed spaces), square metres or equivalent; Built form - which at its simplest tends to be based on plot ratios (% of building in relation to the land area), but also includes type of area (as in the London Plan’s central, urban and suburban); height of buildings and other standards; or Person-based measures, such as persons per hectare.

While I agree that density is often perceived as a negative implication of urban living, could we have a ‘successful housing density index’ - where all residential developments are reviewed through Post Occupancy Evaluation and assessed using the RIBA’s Social Value Toolkit? This would be giving a measure of the impact of design on people’s wellbeing and could be looked at in relation to the development’s density – giving a good indication of successful, or not so successful, densities.

Other questions raised the issue of the physical aspects of buildings, including whether there are limits on height of residential buildings (say to 17 storeys as one of the participants suggested) so not to impact health and wellbeing, and also if courtyards in new developments can still function in a traditional way as ‘a place for children to play and mothers to socialise’.

With regards to the impact of buildings’ height on health, every height and density has its purpose and location. However, the success of living in tall buildings depends on tenure, how the building is designed, internal quality of apartments and the long-term management of the place. While high-rise residential buildings have a place, it is probably only a small place in the proportion of the new homes that we require. It is easier and far cheaper (and I don’t mean ‘cheap’ in a pejorative sense) to design buildings that deliver dense but robust housing at medium heights, and by that I mean a traditional mansion block typology, arranged around a courtyard.

There are other physical aspect of ‘lower buildings’ that can’t be ignored such as more usable balconies (less windy) that increase the sense of connection to the surroundings, whether it’s feeling closer to the trees or seeing the streetscape, or being able to walk up stairs to go to your home rather than relying on lifts. But the main difference will be a fundamentally different typology of building and layout that will encourage more sociability: tall residential buildings create lots of small floorplates, all separated, that are not conducive to creating a sense of belonging.

It is interesting though to consider the impact of the tenure on this point. At Assael we design many Build to Rent developments. Many of these are (or at least include) some tall buildings and there is certainly a compatibility between a BtR tenure and tall buildings. These developments are designed with a strong focus on shared amenities; residents don’t just live in apartments but they ‘own the whole building’. So there might be a communal lounge on the top floor, an outdoor play space on a roof terrace, or a shared workspace on the first floor. Moving around the building and using all of these spaces is encouraged, and part of the way of life of the building.

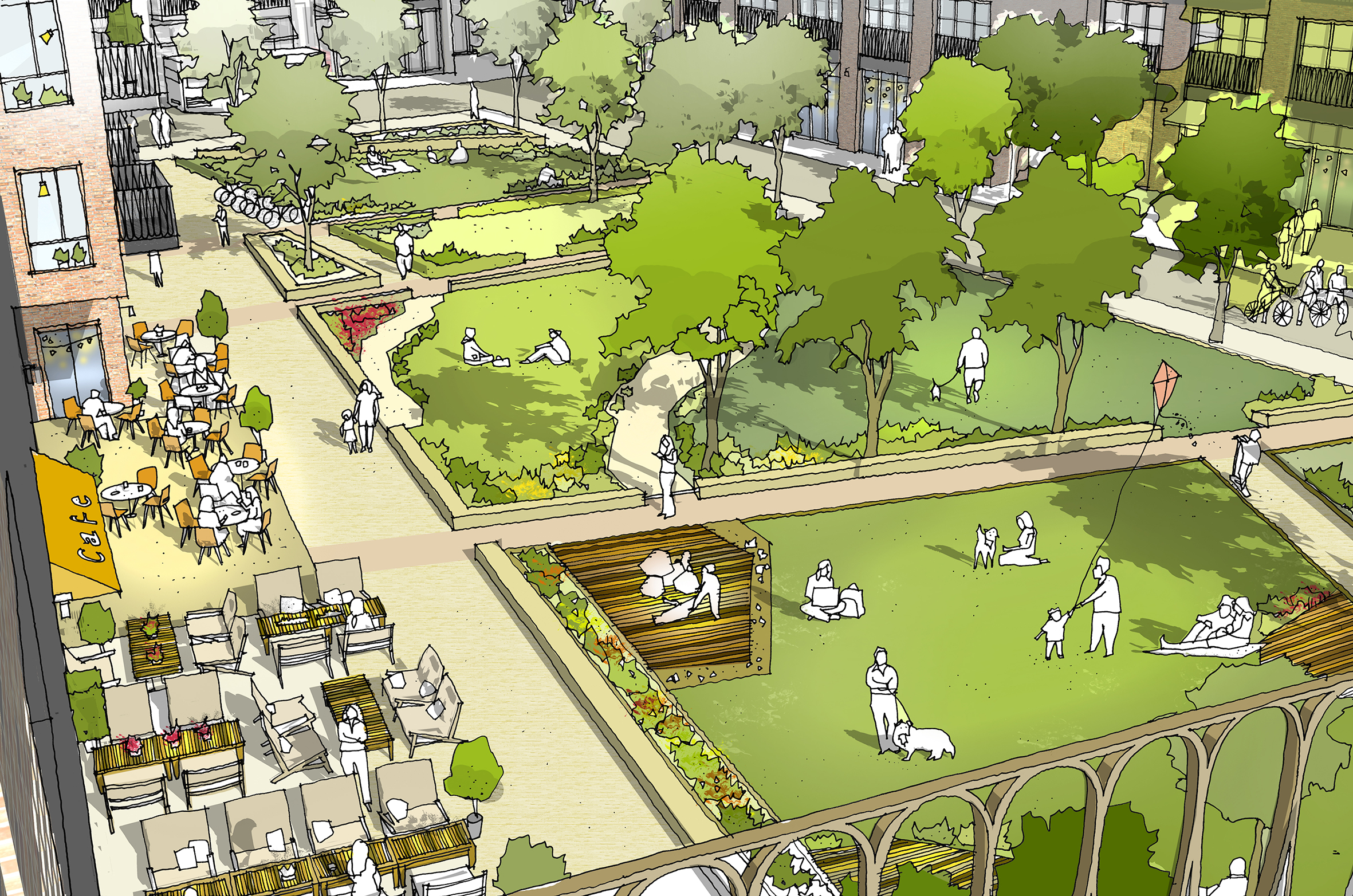

When looking at the function of ‘courtyards’, the question asked was specifically referring to our ‘atomised society’ and changes to social patterns having an effect on the use of space, I think that courtyards are more necessary than ever, providing vital external spaces but also important visual amenity. Courtyards provide outdoor respite for all age groups, at all times of the day. From informal to formal play spaces for toddlers to teenagers, to areas reserved for people to appropriate for community planting, food growing etc. I think traditional courtyards functions are evolving to become less passive, as places just for sitting in, but more actively usable and appropriable, which is certainly a good thing.

I think that urban living will not only remain a necessity but a positive choice, even post-covid. We are in a difficult situation though, with a real need for much more housing and very high land values, effectively meaning that the system binds us to a certain density of housing in existing urban areas at the risk of increasing prices and reducing supply even further. Architects and planners are in a difficult position of having to maximise every site, and frankly sometimes being asked for some magic… But that is the important role we must play, to focus on better quality and design in housing, prioritising people’s health and wellbeing as a non-negotiable parameter in the design process.

Image © Emily Newton, Assael Architecture