Post

Sadiq’s not the only sheriff in town: London’s ever-shifting borough leadership

22 Sep 2021

For many Londoners, Mayor Sadiq Khan is the most recognisable local government figure, but all of the city’s 33 local authorities has its own leader or directly-elected mayor, each of whom plays a vital role in the city’s political ecosystem.

With the next local elections in May 2022 fast approaching, London Communications Agency Chairman Robert Gordon Clark and LSE Professor Tony Travers ponder the causes – and possible consequences – of an unusual amount of churn among this less-glamorous, but no less important group of political leaders.

Leader of what?

To take it from the top, London essentially has two spheres of local government. The Greater London Authority (GLA) is its regional, city-wide authority. That sits alongside 33 local authorities, commonly referred to as boroughs or councils. They have partially overlapping areas of responsibility – and while in some areas the GLA’s powers “trump” those of the boroughs, there are others where the GLA has little influence.

The GLA, or “City Hall”, was established in 2000 and is led by a city-wide directly elected Mayor of London, who plays a vital role as a strategic, regional leader – first Ken Livingstone (2000-2008), then Boris Johnson (2008-2016) and now Sadiq Khan (since 2016). The Mayor has a wide range of powers over areas including transport, policing and fire services, planning, the environment, adult education, public health and more (though the level of these powers vary). The Mayor is scrutinised, within City Hall, by 25 elected London Assembly Members.

But the bedrock of local government in London is formed by its 33 local authorities, constituted in their current form in 1965. 32 of these are London Boroughs – though Kensington & Chelsea, Kingston-upon-Thames and Greenwich carry the grander title of Royal Borough, while Westminster also has the (largely symbolic) distinction of being a City Council. And then there’s the City of London Corporation, a unique and ancient public body whose history and governance are far too complex to explain here in detail.

Now, most of these local authorities are headed up by a leader, a sort of “first among equals” elected councillor who enjoys the support of a majority of fellow councillors, all of whom are elected every four years. Each borough also has a mayor, but they tend to have mostly ceremonial and charitable duties. However, in the case of Hackney, Lewisham, Newham and Tower Hamlets specifically, the voters directly elect a mayor with executive powers. The City Corporation’s equivalent to a leader is the Chair of the Policy and Resources Committee, though it also has a mostly ceremonial Lord Mayor.

It is these 33 leaders and directly-elected mayors who are the focus of this analysis, as crucial but usually unsung figures in the political drama of London politics. Each oversees a local authority which must raise taxes (council tax, business rates and other fees and levies) as well as seek funding from national Government to budget for and run a range of local services spanning planning, education, social care, public health, local roads, waste management and more. Their respective “patch” is not only as big as a medium-sized English town in its own right, but also forms part of Greater London’s closely-woven urban fabric – and so, they must also work closely with their neighbouring boroughs’ leadership, the city-wide Mayor of London and national Government.

Indeed, a borough leader arguably has more power over services directly facing residents, from bin collections to local schools and planning policies, than either the Mayor of London or national Government. This means that the character, experience, and skills of this group of 33 people can have a tremendous impact on the quality of life of every single resident – and on the city inherited by future generations.

Change is in the air

Before and after each election there are always changes to borough leaderships. Some are necessitated by a change in political control, when a new party takes the reins of a given borough during the normal election cycle. Some follow a ‘coup’ within a ruling party’s group, when disgruntled or sometimes just ambitious councillors topple their own leader between elections, through a vote of no confidence or similar. Sometimes, it is through well managed succession planning, with seasoned leaders making way for the next generation in an orderly fashion.

But in a period of just over three years since the last local election in May 2018 through to the summer of 2021, there has been an intense amount of change, more so than in any time that we can recall over the last 20 years. This, we felt, merits some analysis. Why have so many leaders been replaced? What does it mean for the next local election, less than a year away in May 2022? And what does it mean for London as a whole?

2006 - 2018

Looking back briefly, as New Labour headed towards the end of a decade in power nationally, the 2006 local elections in London saw a significant shift away from Labour to the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, leading to six ‘No Overall Control’ (NOC) councils and the best result for the Conservatives in the capital since 1968.

Conversely, the 2010 elections, held on the same day as that year’s General Election – the end of Labour’s 13-year reign – saw a surprise resurgence for the party in London. Local elections in 2014 and then 2018 saw Labour strengthen its political hold in the capital, so that following the May 2018 elections – and to this day – Labour controls 21 of London’s 33 boroughs, close to a record high following the formation in 1965 of the boroughs as we know them today.

2018 - 2021

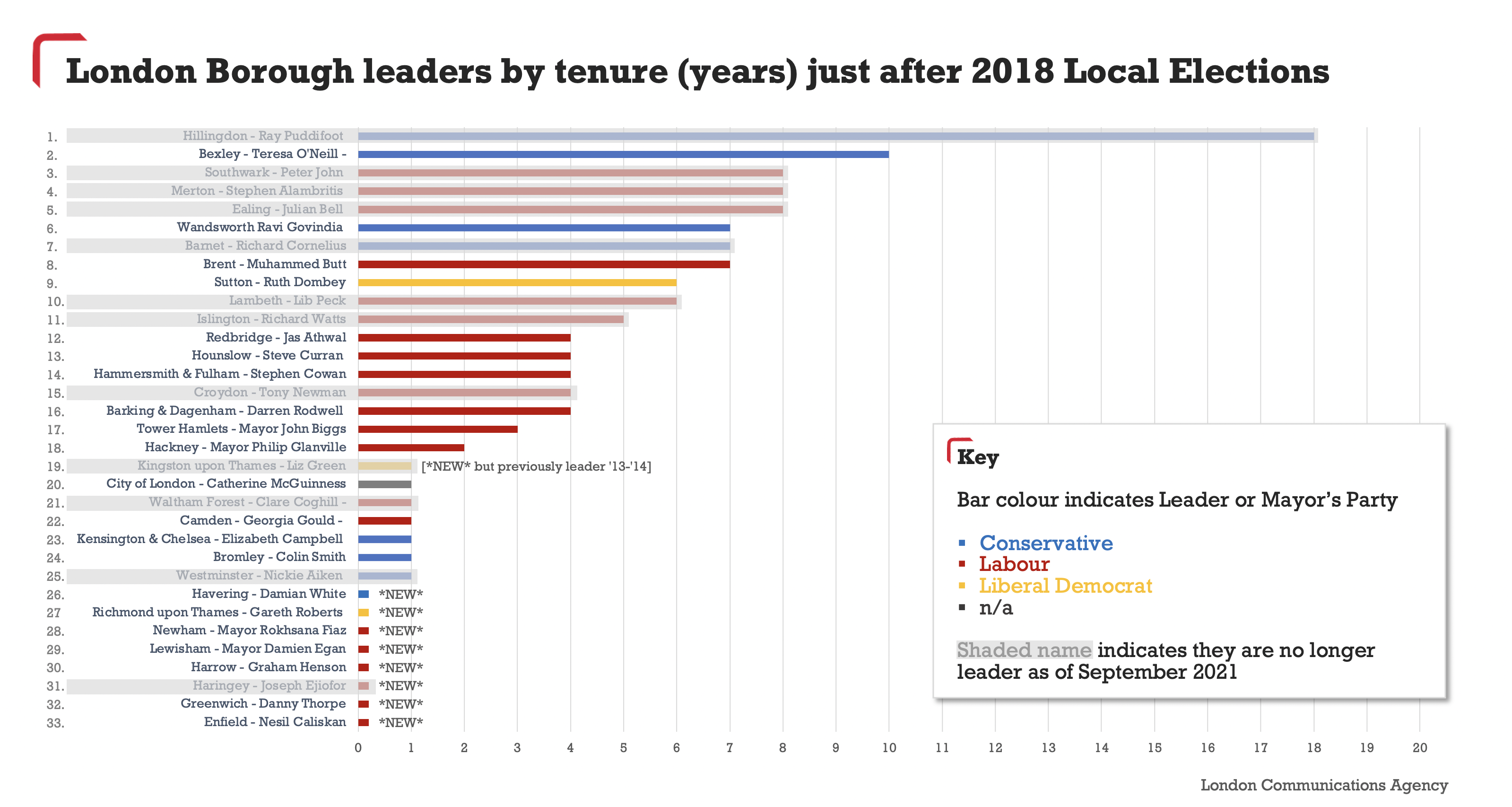

But then, the period immediately preceding and following the 2018 elections saw the beginnings of a prolonged period of leadership change and instability, which has lasted to this day. Chart 1 below shows the leaders of the 33 local authorities in London just after the 2018 local elections.

The 2018 local elections produced six new leaders and two new directly-elected mayors. Rokhsana Fiaz (Newham) and Damien Egan (Lewisham) replaced very long-standing Mayors Sir Robin Wales and Sir Steve Bullock who, between them, had over 30 years’ leadership experience (as leader and/or mayor). Some, such as Enfield’s leader Nesil Caliskan, did not actually lead their group into the election but in her case took over via a challenge at the local party’s AGM that year, replacing another experienced Labour leader, Doug Taylor.

A further seven had become leaders only a year or less before leading their groups into the election, which then consolidated their position. That means that as the dust of the 2018 election settled, nearly half (15 to be precise, from Liz Green in Kingston down on the chart) of the boroughs’ leaders had been in post for a year or less.

This level of change was in itself quite significant, so one might have expected a period of relative stability to follow. But since then, no less than 11 leaders (shaded grey above), or one third of the total, have been replaced (in the case of Lambeth, twice). This includes seven of the longest serving 11 who had led their councils since at least the 2014 elections. Nine of these leaders have stepped down or were replaced after a “coup” over the course of 2020 and 2021 alone.

The combined tenure of these 11 leaders amounts to almost 100 years of experience – and when one thinks of the sheer complexity of the job, that’s quite a lot of experience lost.

2021 - 2022

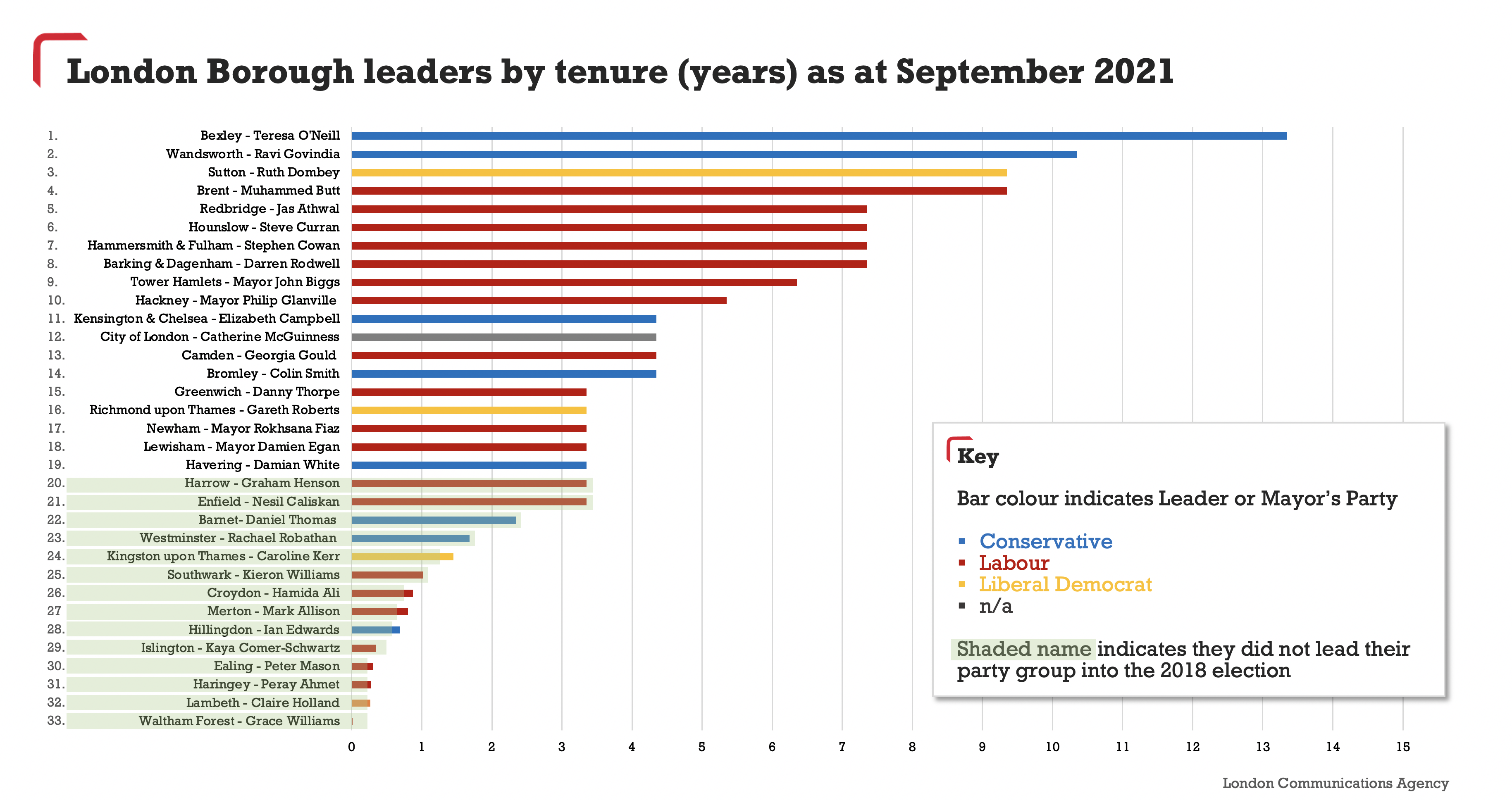

Chart 2 provides a summary of where we now are.

As we run up to the local elections next May, it is worth noting the relative inexperience of many of these leaders. 23 out of 33 have been in post for less than five years and 14 were appointed after the May 2018 elections, meaning they have yet to lead their party in a local election campaign.

WHY SO MANY CHANGES?

There are clearly different reasons for each change.

First, much of the churn has been in Labour boroughs where often very public divisions have been at play within the local party. It may be that this is a natural consequence of the party’s dominance in some boroughs, leading to the eventual appearance of an ‘opposition from within’ – Newham and Haringey, both Labour strongholds, come to mind here.

But the Labour-led boroughs Ealing, Haringey, Lambeth, Croydon and, to a lesser extent, Southwark have all seen political factors played out in the public domain for reasons as varied as Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs), left-right positioning (reflecting national Labour Party factionalism and the ongoing impact of Momentum), the council’s financial management or simply a sense that a leader has “had their turn”.

That said, there are also smoother examples like the change in Labour-led Merton, where Stephen Alambritis handed over to Mark Allison who had served as deputy for most of his 10 years at the helm.

By contrast, the Tories have tended to do things with rather less drama. For example, the change over from long standing Conservative leader in Hillingdon Ray Puddifoot to Ian Edwards had parallels with the change in Merton. However, the transfer in Barnet from Richard Cornelius to Daniel Thomas had its moments and Westminster City Council, arguably the most high-profile of all London and UK local authorities, has seen three leaders in the space of four years (though these were largely a result of career changes, such as Nickie Aiken being elected as the local MP).

Undoubtedly, managing the impact of Covid and Brexit following 11 years of austerity has taken a serious toll on those at the helm. This particular trinity has made the usual job of a borough leader - balancing the expectations and ambitions of their political groups (in some cases nervous about the influence of boundary changes to wards and their “electability” at upcoming elections) with the needs and desires of the wider public - consistently challenging and often impossible.

And as is the case for all politicians, the round-the-clock scrutiny and criticism generated via social media has undoubtedly upped the intensity and required resilience, likely another contributing factor to the shorter shelf-lives of leaders lately.

WHAT COULD THIS ALL MEAN FOR NEXT MAY?

This coming May sees London vote in its next local elections – for the 1,800+ councillors of its 32 boroughs (and for the directly elected mayors of four of these). The City Corporation will be holding its elections separately, two months earlier. These elections will be interesting for a number of reasons, one of which is that there are a lot of relatively new leaders fighting to prove themselves. And while Labour boroughs like Ealing, Harrow, Islington, Lambeth and Southwark are highly unlikely to see a change in political control (although Harrow is especially worth watching), current majorities could be reduced, potentially weakening the position of their leaders, who having been installed between elections will be eagerly seeking a confirmation of their mandate at the ballot box and a full term from 2022 to 2026.

Meanwhile, there are new leaders in at least six key “swing” boroughs, which are comparatively more likely to switch political control (to varying degrees). Labour’s Hamida Ali (Croydon), Mark Allison (Merton) and Nesil Caliskan (Enfield) will all need to find convincing narratives for their manifestos and form the right alliances within their local parties to keep a viable working majority. Rachael Robathan (Westminster) and Daniel Thomas (Barnet) will be doing the same for the Conservatives, as will Caroline Kerr for the Lib Dems (Kingston).

And whilst experience is clearly a vital ingredient in political campaigning, we will of course be watching closely historic Tory strongholds like Wandsworth, where Ravi Govindia is now the capital’s second longest-serving leader but faces another tight election battle with Labour, and Bexley, where Teresa O’Neill (now the longest-serving leader in London) seeks to further consolidate the Conservatives’ strength.

AND THEN AFTER THE LOCAL ELECTIONS?

If incumbent leaders win with a decent margin, they will take that as a mandate to “keep calm and carry on” – doubling down on established agendas, policies and messages. In most places, that will probably be a good thing, as a lot of complex policies need time to be properly implemented, monitored, and tweaked before they work as intended.

If the current leaders don’t do as well as their parties’ local activists are expecting, but the incumbent party still holds on, we might expect some challenging Annual General Meetings (AGMs) immediately after the election – possibly heralding changes of policy and perhaps also of leadership.

Also critical are the outcomes of the directly-elected mayoral contests playing out in Newham, Hackney, Lewisham and especially Tower Hamlets where Labour may be facing a challenge from local party Aspire – led by former Mayor Lutfur Rahman, who was stripped of his mayoralty in 2015 following an investigation into electoral fraud. Before then there is also a referendum this autumn in Croydon, which may also introduce the mayoral model there.

Ultimately, the individual and cumulative experience and aptitude of London’s borough leaders will play a huge part in how our city is run in the next four years and beyond, so we will continue to keep a close eye on the survivors – and those less fortunate.

Robert Gordon Clark, Executive Chairman, LCA

Prof Tony Travers, LSE

An earlier version of this blog was first published on the London Communications Agency website, in July 2021. This version differs mostly in offering a more detailed explanation of key terms and events.