Post

JOURNAL 2021: All Change at Docklands

4 Jun 2021

Glenn Howells takes us on a historical journey of London’s Docklands and his practice’s involvement in its future

This article is taken from the 2021 edition of the Journal of the London Society. You can find out more about this year's Journal here. Or join the Society for just £10 and receive a free copy.

Until the late 1960s the Docklands were a thriving and vital part of London’s economy, generating a raft of associated industries among the networks of wet and dry docks and yards, and employing thousands of the city’s workers. The development of Tilbury further downstream as a major deep-water container port in the mid 1960s, equipped to deal with larger vessels and containerisation, was the death knell for the area, and from 1960 to 1980 all of London’s docks were closed, leaving around eight square miles of derelict land. The 1980s heralded the regeneration of the Docklands, led by the DLR and most notably Canary Wharf, but this stopped short at the Isle of Dogs.

We first started working in London’s eastern Docklands in the depth of the banking crisis of 2008, when we were asked by developer Ballymore to look at a string of sites, stretching east from Leamouth Peninsula to either side of the Thames Barrier. Our brief was broad, to look at the potential in these sites, and see if development was viable, at a time when land values were in freefall and funding for property near impossible.

What became evident very quickly, was that up until this point, Thames-side developments east of Canary Wharf had been brave but opportunistic. Surrounded by working wharfs and warehouses, residential developments had been largely isolated, and gated. Such developments relied on being cheaper than those in established districts further west, the provision of secure parking, and maximising their only asset, the Thames. This led to what appeared to be Torremolinos on Thames; disconnected housing schemes, all straining their necks to give every home a glimpse of the water with little, if any, consideration of sites adjacent. The result of this is still evident; largely dormitory settlements that lack integration, connectivity and a sense of place.

A great positive to come from 2008 was the pause brought about by that crisis, much like we are experiencing today, affording time and scope to reflect, and to think on things differently. Not only did architects and developers begin to look at things differently, but so did public agencies.

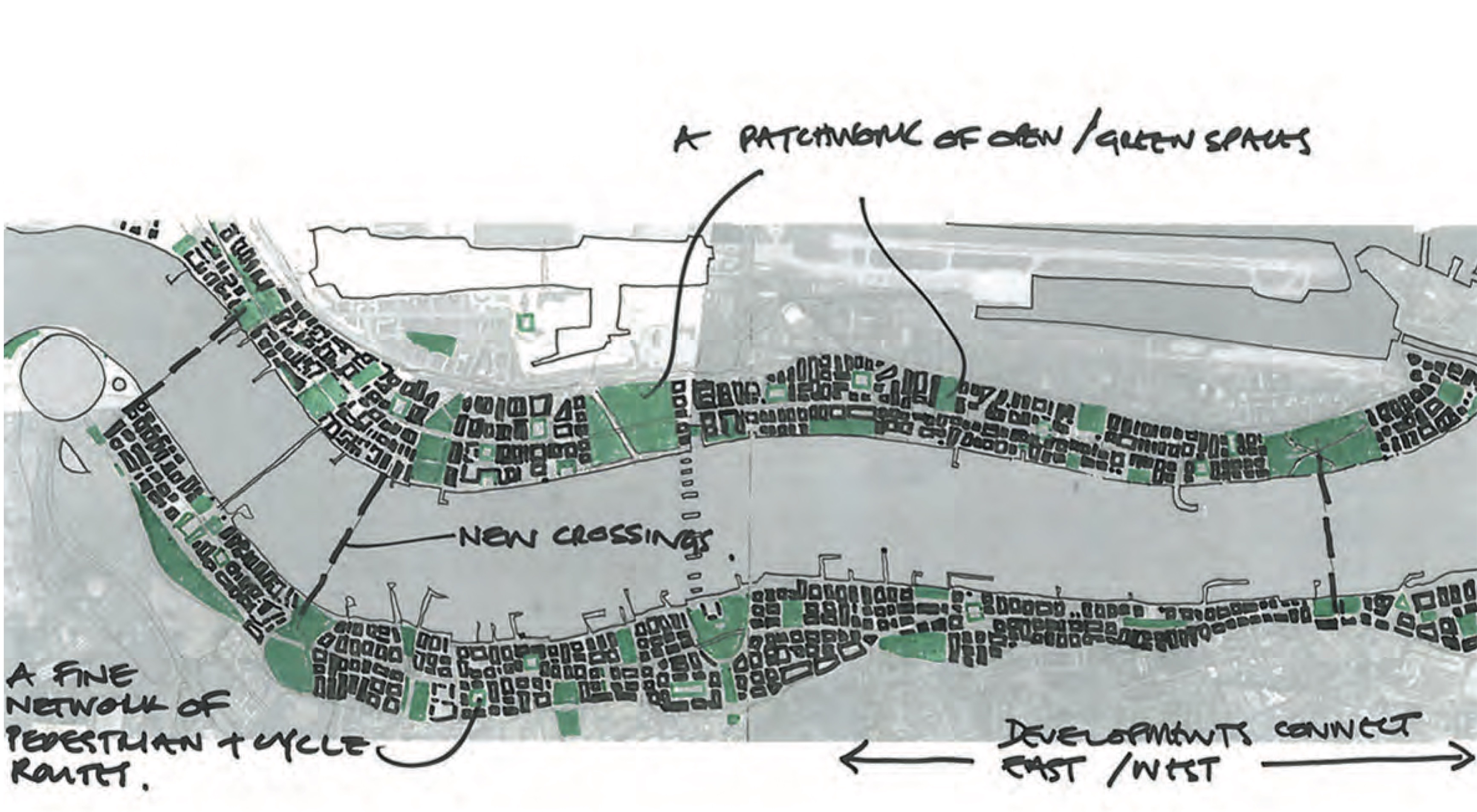

Just as we began to explore with Ballymore the idea of looking beyond these isolated commuter developments to an integrated urban tapestry - potentially a new great estate for London - we began conversations with local authorities, and in particular, Newham’s inspirational new head of regeneration, Clive Dutton. Together we began to imagine a connected district, running from Barrier Park West to Canary Wharf; 5km of walkable, cyclable aspirational riverside developments. A district made up of communities that were proud of the area and invested in it. A district looking out onto the river, but with an inner life all of its own, something that is beginning to emerge today.

The first site to undergo transformation within this tapestry was Royal Wharf; 17 hectares of contaminated land with over

a kilometre of river frontage, at this point blocked to the east by Barrier Point and to the west by the Tate and Lyle works. On this project, we were given the backing of Ballymore, Newham and the GLA to think big and develop an open-ended plan that could, over time, be extended beyond the current land ownership in order to defy

the recession and create the new homes so desperately needed in the capital. To date, over 4,000 homes have been delivered at Royal Wharf, ranging from starter homes to four-storey townhouses, alongside a school, workspace, a new Thames Clipper station and two fully integrated parks.

The next part of the tapestry we were asked to look at was Leamouth Peninsula, now London City Island, an ambitious masterplan by SOM that had come to a halt with the financial crash. After a period of exploration with Ballymore, Tower Hamlets and creative placemakers, cultural strategists and landscape designers, an idea emerged. The idea was for a bold cultural development; replacing costly parking podiums with active creative workspace, drawing people to live, work, and learn on the Island, and creating a diverse range of activity throughout the day.

A pivotal point for this project was attracting English National Ballet to the Island; an innovative partnership with Ballymore that has fulfilled the ambitions of the company’s English National Ballet School to create a world-class centre for dance, whilst creating a cultural anchor for the Island - one that has not only animated the Island but attracted other creative organisations, such as the London Film School, to locate there.

After almost 15 years of working here, we are very proud to have played a part in unlocking the potential of this part of London. In particular challenging the silo approach to sites that had led to disconnected dormitory projects, and helping to plant the idea for this wider tapestry that stitches this part of the riverside together, connecting existing, new and future communities.

Importantly, it is clear that for this part of London to really succeed it needs to have more than excellent and affordable housing. It needs the workspace, education, parks and culture that will make it a place that people do not just pass through, but a destination where people come and settle for good.

Glenn Howells is the founding Partner of Glenn Howells Architects, a practice established in 1990. It has won national and international design competitions with its portfolio ranging from cultural buildings and housing to larger scale, urban mixed-use developments.