Post

International Women’s Day: New map celebrating women’s history in London

7 Mar 2024

By Katie Wignall, founder of Look Up London and Blue Badge Tourist Guide.

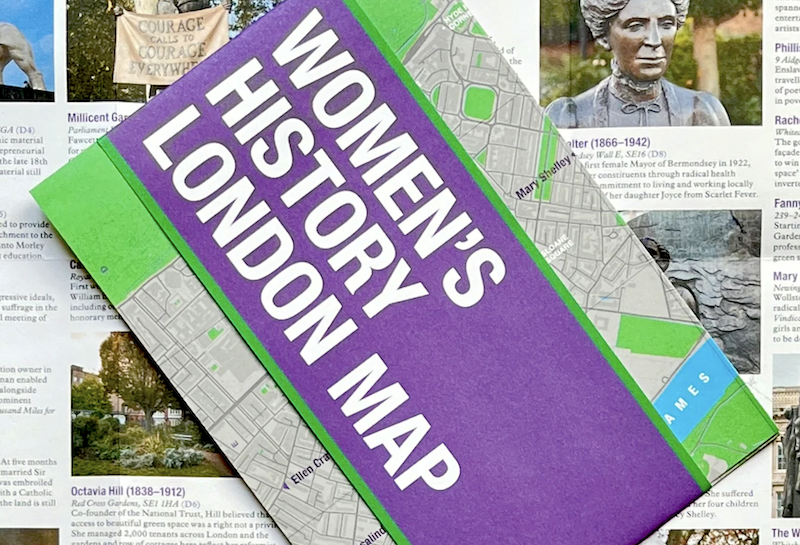

A new women’s history London map from Look Up London, highlights 50 statues, sculptures, blue plaques, gravestones, buildings and monuments – dedicated to women such as Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Virginia Woolf, Aphra Benn, Ada Lovelace and Phillis Wheatley.

With original photography by Jo Underhill, the map guide is a companion to begin exploring the lives of some of London’s most impactful women, and to inspire the next generation to continue their work.

A woman who changed the look of London (and beyond) is Eleanor Coade. This 18th-century businesswoman ran an "artificial stone" factory in Lambeth from 1769.

Check out our rundown of upcoming events

Even if you’ve never heard of Eleanor Coade, you will have almost certainly walked past some of her work in London.

Born in 1733, Eleanor Coade would become one of the most successful entrepreneurs in the 18th century, change the face of manufacturing and leave a lasting visual legacy across London, the UK and beyond.

In April 1759 her father went bankrupt. The family (George, his wife Eleanor and the two girls, Eleanor and Elizabeth) went to London. In 1762 George is recorded as living in Charterhouse Square, and by 1766 Eleanor is working as a linen draper.

In 1769 disaster struck again when her father died. That same year Eleanor (now 36) and her mother bought an ailing artificial stone factory which was previously run by Daniel Pincot.

This might sound unusual for an 18th-century mother and daughter to embark on a business together but there was a history of entrepreneurial women in the family. Eleanor Senior’s mother was Sarah Enchmarch who ran a successful textile business in Tiverton, Devon. You can read more about her here.

Daniel Pincot owned a factory at the King’s Arms Stairs, Lambeth opposite Whitehall Stairs.

Subscribe to the London Society newsletter

It’s hard to ascertain the exact business agreement but within two years this ‘partnership’ had unravelled. On 11 September 1771 an advertisement appears which states:

‘WHEREAS Mr Daniel Pincot has been represented as a Partner in the Manufactory which has been conducted by him; Eleanor Coade, the real Proprietor, finds it proper to inform the Publick that the said Mr Pincot has no Proprietry in this Affair; and no Contracts or Agreements, Purchases or Receipts, will be allowed by her unless signed or assented to by herself.’

Three days after this public burn Mr Pincot was fired from the factory. Not much is known about his later life and he was buried in Bunhill Fields in 1797.

The Lambeth factory appears on the 1799 Horwood Map, the ownership of the factory clearly indicated with “COADE’S Artificial Stone Manufactory” written across the buildings.

Though Pincot and Coade clearly didn’t get on, another staff member would prove a far better partner.

John Bacon was born 1740 in Southwark. He had previously been working with Pincot because they were both named on a trade card together. In 1769 he won a gold medal at the Royal Academy and the following year would become an associate member of that same illustrious Academy.

One of his most famous works in Coade Stone is the reclining figure of Father Thames outside Ham House. Created in 1775 It’s over seven-feet long and had to be fired in separate parts, then fixed together with iron rods.

Creating an artificial stone

Eleanor Coade wasn’t the first to create an artificial stone, the hunt for a cheaper and more durable material had been underway since the 16th century.

However her factory could consistently provide durable, intricate designs that were highly adaptable and they succeeded where other, similar, factories failed.

The process was time-consuming and required highly skilled workers at almost every stage.

After an artist created a clay model (slightly bigger than the original to allow for shrinkage), the mixture was poured inside. It was then fired for four days in a coal-powered kiln while watched over closely at all times. If it was a large piece it would then have to be reassembled and then finished and smoothed.

Because of the complex process and the fact no records survived, it was only in 1991 the ‘recipe’ was finally revealed. Getting technical, the mix included: 50–60% ball clay, 10% grog (which is finely-ground, pre-fired stoneware) 5–10% crushed flint, 5–10% fine quartz or sand, and 10% crushed lime soda glass.

However the real genius of Coade’s factory wasn’t that it used a special “secret recipe” or “ingredient” but rather the vast knowledge and scientific experiments that allowed them to continually adapt the mixture dependent on the size and variety of commissions.

This is probably why Eleanor Coade never patented her ‘recipe’ and really the product itself was only part of the reason for her wild success.

Marketing and publicity

As we’ve seen from the advertisement above, Eleanor Coade was certainly not shy about promoting her business and herself as a businesswoman.

I particularly enjoyed a trade card/advert in the British Museum’s collection which shows Hestia, the Greek Goddess of the hearth and a winged Father Time. Time, who’s trying to manhandle the fine sculpture in the centre is being firmly shoved away by Hestia, this suggestion being Coade stone withstands all that time and age can throw at it!

At first Mrs Coade (she never married but this title conferred respect in Georgian society) called her product “Lythodipyra” which is Greek for stone fired twice. Quite the mouthful, this was soon phased out for the much easier to pronounce Coade Stone which was stamped on all the products.

This might sound obvious today, but this type of branding wasn’t seen in other competitors’ work.

Further proof that the factory was a well-known landmark is its inclusion in a 1791 engraving of Westminster Bridge by John Edy.

Another way to reach more people was by printing catalogues (the 1784 version had 788 different designs!) and it’s these cheaper ‘off the shelf’ Coade stone decorative elements that are most common today. They can often be see in keystones faces on surviving Georgian townhouses. Some of the greatest examples in London can be found in Bedford Square.

Where to find Coade stone in London

As well as the instances listed, there are plenty more examples of Coade stone to track down in London. I’ve picked out some of my favourites.

At 80-82 Pall Mall there are two muscly figures supporting the porch of Schomberg House. These were designed by John Bacon.

Another statue which is partly made of Coade stone is the mysterious figure of Alfred in Trinity Church Square which you can read more about here.

One example that isn’t as widely celebrated, but really shows what Coade stone could achieve, can be found in Greenwich’s King William Courtyard.

Known as Nelson’s Pediment, this was created at the Coade manufactory and designed by Charles Panzetta c.1812. It was based on Benjamin West’s painting, ‘The Death of Nelson’ 1807 and shows Britannia accepting the dead naval hero.

The end of Coade stone

Eleanor Coade died in 1821 and though the factory continued until the mid 1830s, a combination of the death of the founder and changing tastes meant the factory didn’t survive.

However, thanks to the durability of Coade stone itself there are hundreds of examples which are mapped on the Historic England website here.