Post

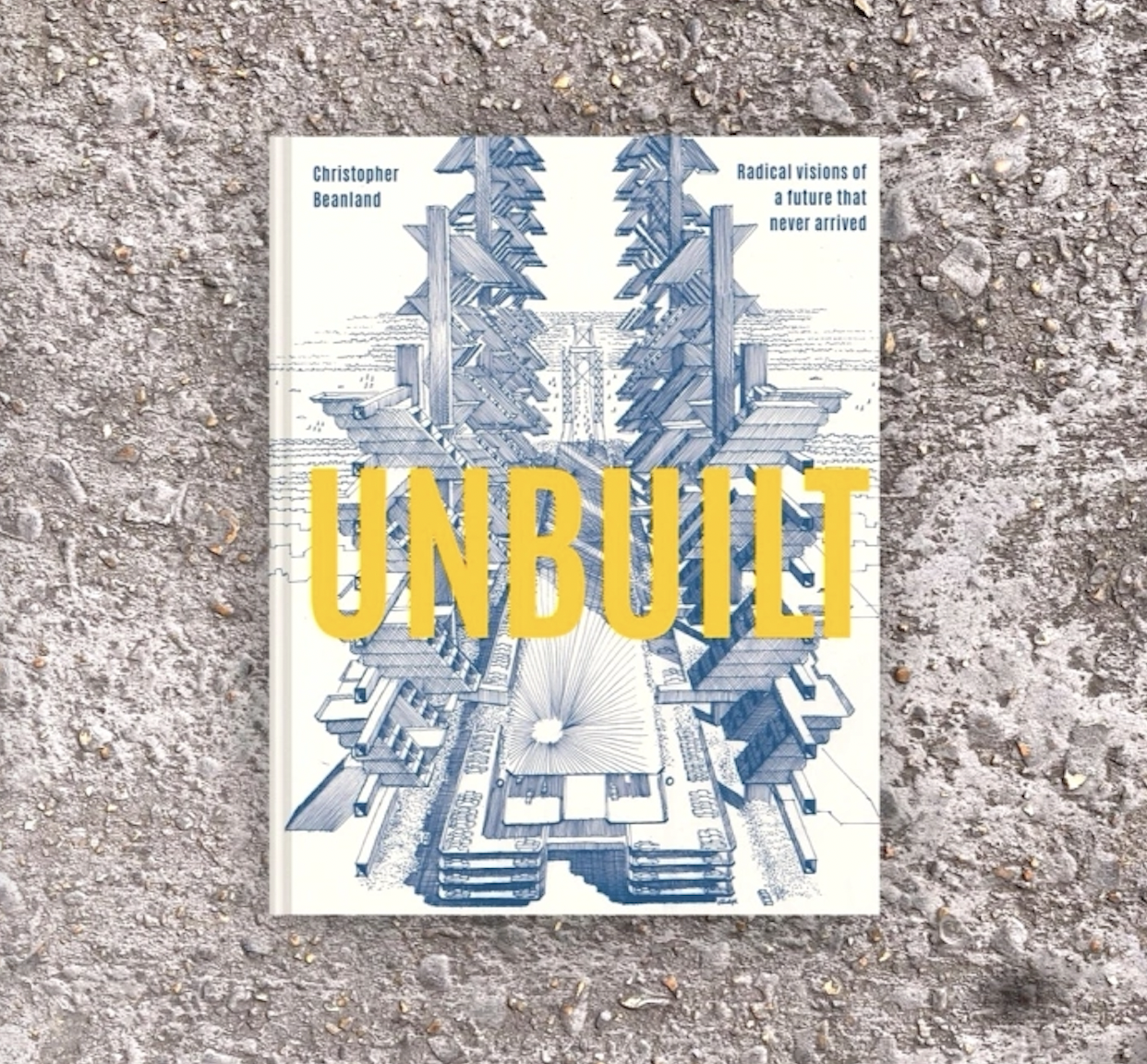

BOOK REVIEW | UNBUILT - Radical visions of the future that never got built

24 Jan 2022

Reviewed by Rob Fiehn

UNBUILT: Radical visions of a future that never arrived by Christopher Beanland provides an insight into many of the ‘what if’ questions we sometimes pose ourselves when thinking about the development of our cities and neighbourhoods. It spans a host of ideas and proposals that were put forward since the start of the 20thcentury and encourages us to think about how these concepts could have impacted our lives and reshaped the built environment. They run the gamut of the sublime to the ridiculous, often calling into the question some of the great visionaries of the modern age.

While the book has an international outlook, I am drawn to those schemes that affect London, my home town and current city of occupation. I can remember a version of Kings Cross that constituted a centrally-located wasteland, given over to industrial purposes and a sprawling railway that seemed to gobble up far too much space. It could have been very different if architect Charles Glover had got his way in the 1930s and built a circular airport with no less than eight runways, arranged like a cartwheel. We might scoff at this idea now but is it really so strange to consider as we head to a potential future, dominated by drones and the possibility of flying taxis? It’s hard to imagine an international airport sitting in the heart of London but Glover’s plan could well resurface in a more contemporary iteration but probably not on top of today’s Kings Cross, with its plethora of contemporary offices, homes, eateries and the arts university.

The Fun Palace, designed by Cedric Price for theatre director Joan Littlewood, could have given London its own Pompidou Centre, a decade before such a cultural proposal was made for Paris by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano. An endlessly adaptable space, it would have provided space for an ever-changing theatre and other arts organisations. It also feels fitting that such a feat of engineering should have been attempted by British architects and engineers, who were at that time pushing the boundaries of what was technologically possible. Instead, Price’s plans were left on the drawing board but they clearly influenced a generation of designers and still appear radical today.

I also have a soft spot for the pedways of London, and can often be found wandering the small elevated circuits in the City. Beanland shows us that this modest set of walkways connecting the Barbican to Moorgate could have been an interconnected series of raised routes criss-crossing the Square Mile. Anyone that has been to Hong Kong will know the joys the making your way across an urban expanse via dedicated pedestrian routes can be thrilling. Not only do you look forward to finding out where these circuitous passageways will take you, but you are also afforded unusual views at such a height. It is freeing to be one step removed from the hustle and bustle at street level and there are even moments of serenity that can be found when stopping to take in the view of a park or sometimes ruin (if you’re anywhere near London Wall). I would welcome the return of the pedway and indeed there was a recent extension to the City walkways, when Make Architects finished their work on London Wall Place in 2018.

In this review, I have skirted over a few London examples that tickled my fancy but they are far from the most outlandish and grandiose of the unbuilt projects in this book. It’s a fantastic survey of 20th century architectural ambitions and it has a lot to tell us about contemporary attitudes to city making and awe-inspiring design.