Post

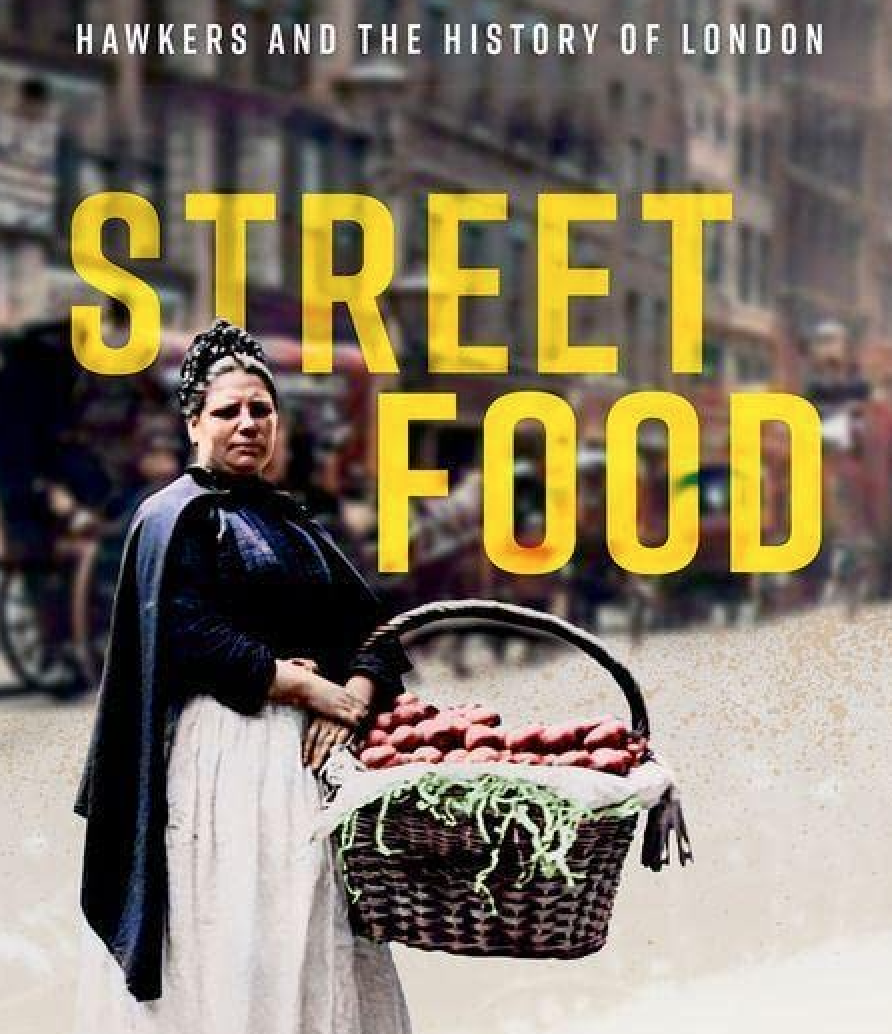

BOOK REVIEW | Street Food: Hawkers and the History of London

10 May 2023

Charlie Taverner, Oxford University Press

Review by Diane Cunningham, Society Trustee

Street Food traces the history of London’s street traders starting from the sixteenth century and bringing things bang up to date with the impact of the Covid-19 lockdowns. It takes us through the people involved, the food, the ‘cries’ which evolved into terms still in use and the challenges facing traders from housing to traffic, broken pavements, and their reputation. It places street trading and markets in the context of a changing city with a diverse population that adapted frequently.

The book shows how the origins of street trading were key in setting up the foundations of today’s markets, particularly as street trading appears to have started in the area which remains home to many of London’s oldest markets around Whitechapel and Petticoat Lane and Whitecross Street.

The nature of street trading was informal work and trade varied depending on the weather, the number of customers and other events taking place. This can still be the case now as it did centuries ago. More women than men were street traders however, being a hawker wasn’t seen as a formal job and many lived in low-quality housing in the poorest parts of the city and suffered from a reputation, one of operating on the edge of the rules. By the 1890s it became more recognised as a profession and more of a family model started to take shape with younger people helping out parents or taking on another stall.

Originally, the produce sold came from the Low Countries and France until Kent, and parts of London took over from the mid-sixteenth century as plots were dug on the side of the Thames which supported a growth in market gardening. This changed in the nineteenth century when hawkers were allowed into the wholesale markets, such as Billingsgate and Smithfield, to buy their stock directly from the market traders. At first, this was frowned upon, but there is a suggestion that their custom helped reduce waste as if all the fish, meat and other produce were only sold within the markets, there was too much of it.

Street trading provided access to food in the capital, both in serving better off residents with higher end produce door-to-door and for the hawkers to be able to buy low-cost products which they could sell to people on lower incomes on the street. In some cases, people couldn’t buy produce anywhere else, or they lived in areas where there were few food shops. It also established a model for the milkman and fish deliveries which are still operating in a similar format today.

Today’s street food revival is linked back to the financial crisis of 2007-8 which led to more casual dining driven by cost, people sometimes starting new careers with informal pop-up-style kitchens and an increase in the variety of the food available in London. The difference between street food now and then is that kitchen facilities and space in homes for preparing or cooking was limited, meaning that street food existed to cover meals from breakfast to dinner and throughout the working day, more for sustenance than an eating out experience.

Many markets are now curated and regulated much more than they were, and often for good reason, but the author argues that London may have become less lively as a result and with many of them banning ‘cries’ / shouting from the stall in the traditional sense.

I spend a lot of time at markets both for pleasure and for work, so this book particularly resonated with me. However, it will be enjoyed by anyone who wants to learn more about London’s history, its neighbourhoods and the role that markets and street food played both in the past and present.