Post

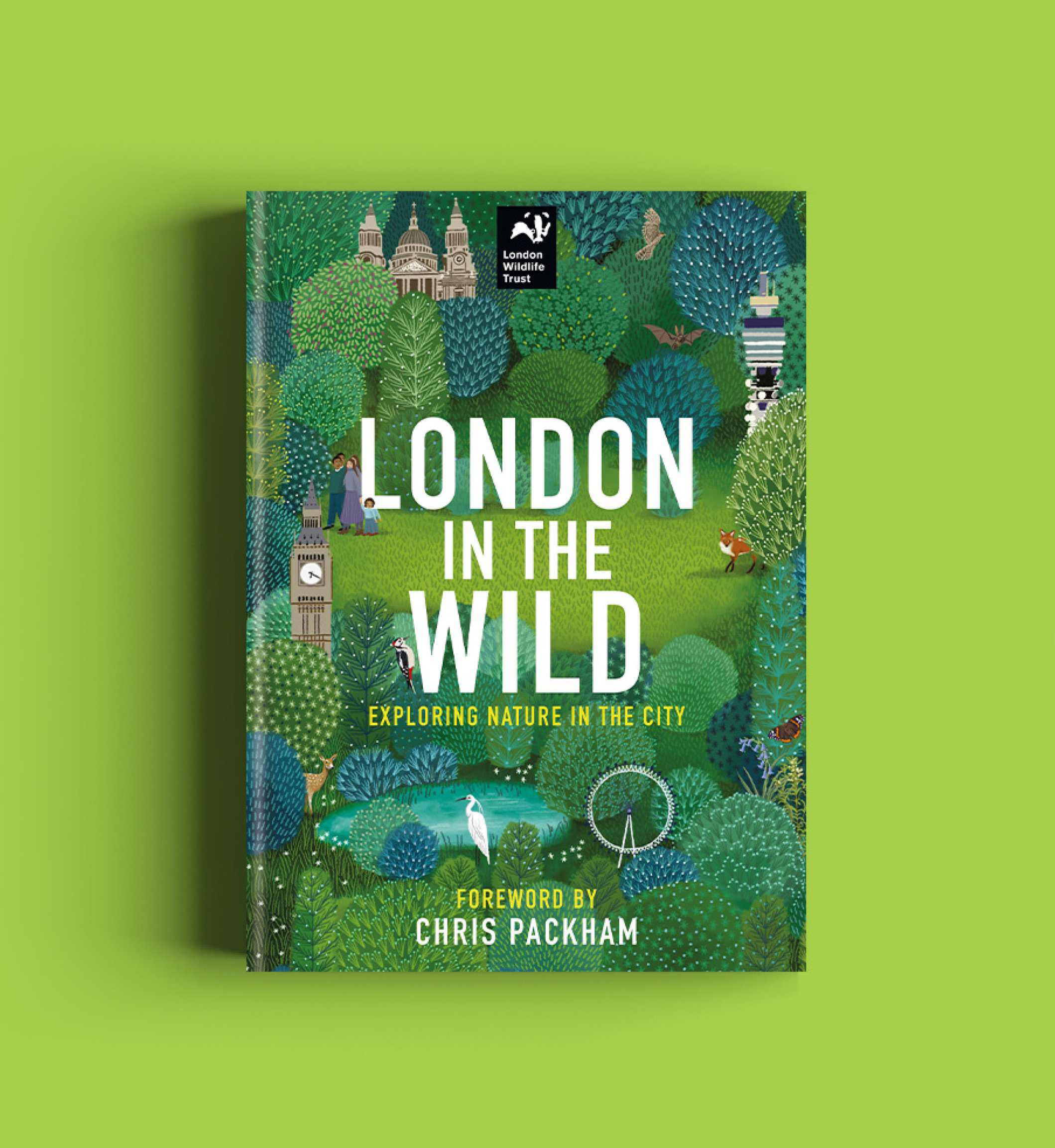

BOOK REVIEW | London Wildlife Trust – London in the Wild: Exploring Nature in the City

2 May 2023

Reviewed by Steven Heywood

Published by Kyle Books, 2022

A journey down the river Thames opens this new collection from the London Wildlife Trust and proves a good summary of the approach taken, winding past the more artificially created nooks and crannies of wild space in central London before drifting past the tributaries at Deptford and Barking, and out to the estuarine landscapes of the Darent and Gravesend, as the river flows out into the North Sea. Each spot offers something different in terms of the habitats it provides for the myriad forms of wildlife that silently and not-so-silently occupy the margins of our capital.

The book itself meanders like a river, skipping between a number of forms. At times it acts as a primer for wildlife that can be found in the capital, running through the various flowers, birds, rodents, and insects one might find in a particular kind of habitat, and offering a taste of more unexpected stories such as the deer that have started taking up residence in a housing estate near Romford.

At other points it becomes a guidebook to those habitats around the city, interspersed throughout the themed chapters and also collected in a penultimate chapter setting out ten ‘hidden gems’. This is an excellent resource that stands as a useful guide to some lesser-known spots. Some of these are fairly extensive tracts on the edges of London, but others are demonstrations of how wild space can be squeezed into the tightest spots – such as Bow Creek Ecology Park, sandwiched on a spit of land between housing developments in Tower Hamlets and Newham, and now a great location for waterfowl after the possible human uses were exhausted once the Docklands Light Railway tracks started running through this narrow peninsula.

Elsewhere things get more polemical. Sourabh Padke’s section on community gardening is a highlight, arguing that gardening is a collaboration not only with our current neighbours, but with human and non-human neighbours stretching back countless generations who have tended the soil, looked after the seeds, and bred the plants that we have available to us today. Through those links it makes to the present and the past community gardening, for Padke, can ultimately be ‘an indication of our collective commitment to building a more compassionate culture’. And sometimes a simple fact will do just as much as a well-reasoned argument to convince us of the damage that has been done to wildlife, and the importance of trying to restore some balance – such as that London’s hedgehog population has declined from 30 million in the 1950s to less than a million today.

London in the Wild is more of a book for dipping into now and then, rather than something to sit down and read cover to cover – the book is loosely organised into chapters based around different types of habitat, but there’s no clear format for each chapter and the collection of authors have evidently been given fairly free rein to present their enthusiasms. Ultimately, this creates an enjoyable and informative miscellany of the way wildlife persists in an increasingly urban environment, and a timely reminder of the intrinsic value that it holds and the pleasures that it can bring to us.