Post

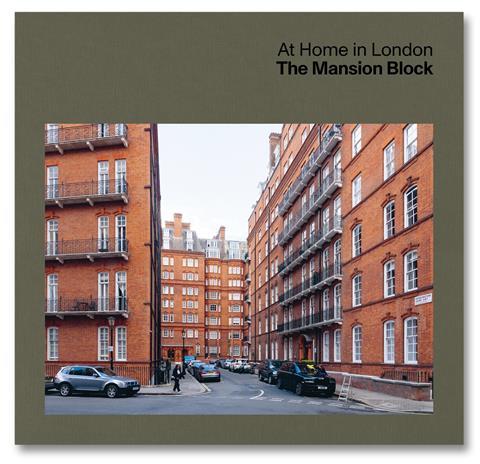

BOOK REVIEW | At Home in London: The Mansion Block

19 Sep 2023

By Karin Templin

Reviewed by Andrew Beharrell

My childhood impression of London was formed by visiting my grandmother in her rented mansion flat near Sloane Square, with its bay-windowed front rooms and small dark service corridor. When I first came to London as a young architect, I lived in mansion flats from the 1890s and 1930s. I have always thought it the best model for inner urban living, and I opened this book with keen anticipation.

Check out our rundown of upcoming events

Karin Templin’s informative and stylish book provides an overview of London’s popular contribution to modern urban living, the mansion flat. Handsomely illustrated with new and historic photographs and specially commissioned plans, the book more than justifies its cover price. However, the reader has to work very hard to understand the plans without a room key or clear distinction between flats and common parts.

It is arranged into three time periods, which the author identifies as golden ages for mansion block development: 1852-1903, 1930-37 and 2010-22. Each comprises an essay and nine case studies, with short descriptions and generous illustrations. They are bookended by two thematic essays, one being a historical overview and the other a summary of mansion block types and variants.

What is a mansion block? Karin Templin’s definition embraces mid-rise street-based blocks ‘where the massing and composition of the facades give the appearance of a unitary and even palatial building with…a noble metropolitan character’. All this dovetails with the present government’s desire to create streets and deliver ‘gentle density’, expressed through the landmark report Living with Beauty (2020), which features one of my favourite mansion blocks, The Pryors on Hampstead Heath, where urbanity meets nature.

The mansion flat, as its name implies, was until quite recently reserved for the more prosperous end of society. This book is not about philanthropic and later council housing for the working class, even though London councils are today some of the most enthusiastic developers of mansion blocks. The author reminds us that the early and middle periods of mansion block development were about private sector flats for rent, and closely prefigure London’s current boom in build to rent. Many also included extensive hotel-like common amenities, like today’s co-living developments.

The early case studies mainly focus on the familiar grand mansion blocks of Victoria, Kensington, Marylebone, Maida Vale and Battersea Park. They memorialise two extraordinary schemes demolished in the 1970s: 13-67 Victoria Street, a near perfect example of Parisian-style flats over shops, and Queen Anne’s Mansions, an austere 13-storey behemoth which loomed over St James’s Park showing that ours is not the first generation to put commerce before context.

The case studies from the 1930s are typically up to ten storeys, pushing ‘mid-rise’ to its limits as architects do today, and they often occupy complete urban blocks. There is great formal and organisational invention around courtyards, setbacks and angular facades. The daddy of them all is Dolphin Court in Pimlico, a complete neighbourhood of 1,310 flats and every possible amenity. Fans of P. G. Wodehouse will enjoy learning that its architect was called Jeeves and that it included many ‘bachelor flats’. I remember a friend’s stern and elderly father warning him about Dolphin Court’s rather louche reputation.

The final section brings us up to date with the ‘revival of the mansion block’ in response to London’s current housing demand, shaped by the Mayor of London’s Design Guide and illustrated with nine handsome case studies. Maccreanor Lavington’s South Gardens is my personal favourite, with its skilful attention to making every flat a comfortable home, and subtle homage to Victorian form and detail.

I must take issue with the assertion that the mansion block revival began in 2010, when some practices have been building ‘modern mansion blocks’ continuously since the 1980s while evolving a new contextual language prefiguring the New London Vernacular. The decision to focus on three precise periods of mansion block development helps give this book its clarity and concision, but inevitably begs unanswered questions about the periods in between, when development did not simply stop as implied by the author.

Get priority booking on events - join The London Society

The author closes by wondering whether this is ‘a new dawn’ for the mansion block. I sincerely hope so, but architects face a huge challenge in developing new apartment block typologies which comply with the latest technical requirements for environmental sustainability and fire safety – none of these examples would do so.

The Greater London Authority now expects 100% dual aspect flats, and Building Regulations Part O also favours cross ventilation. The latest requirement for two staircases in blocks over 18m (typically six storeys) further rules against the traditional mansion block layout of a small number of flats around a compact core. I look forward to seeing inventive solutions in the next edition.