Post

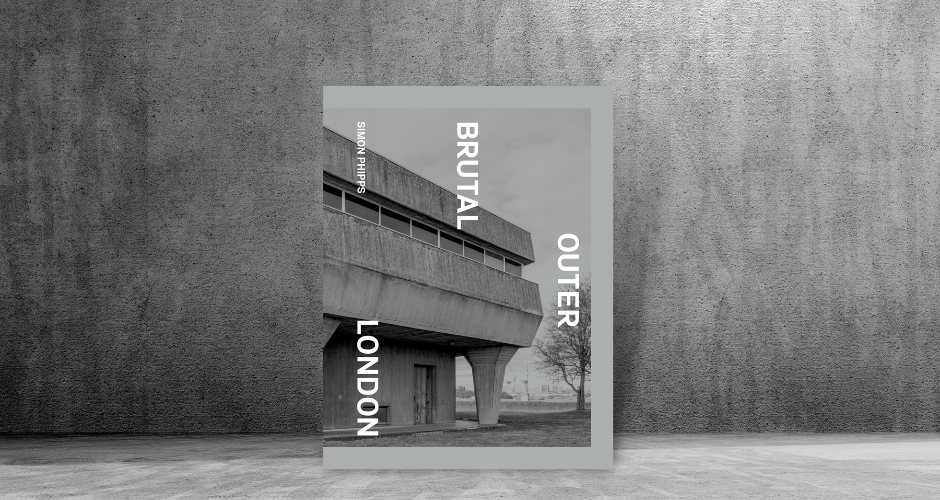

BOOK REVIEW | Brutal Outer London

13 Mar 2023

Reviewed by Mark Prizeman, Society Trustee

By Simon Phipps

This tightly bound collection of photographs covers the flowering of ‘brutalist’ architecture in the outer boroughs of London. Phipps is an accomplished photographer in black-and-white and has also chronicled the modernist architecture of Manchester for ‘The Modernist’, an active Manchunian society relocating a strong appreciation of the younger generations for the fundamentalist modern Architecture of Britain known as “Brutalist’.

The word comes from the Corbusian term “Beton Brut” - bare concrete but also takes in the wine trade word for dry wine and even that rather nasty aftershave advertised by the boxer Henry Cooper. Brutalism is a particularly English post-war distillation of modern architecture, a continental style that had very few built examples pre-war in the UK. The logical extreme and sculptural purity of thistle was enthusiastically nurtured by the council committees and planning departments of Britain. The ‘white heat of technology’ combined with the logical aesthetic of a Churchill tank, completely unsexy compared to the continental offerings it met in battle, created a new style of architecture with which to reimagine and rebuild Britain. Even the American modernist Architect Louis Kahn failed to accommodate the rigour as laid down by the young Peter and Alison Smithson in their 1954 seminal Hunstanton School, the first Brutalist building.

In 1955, The Architectural Review published “Outrage”, Ian Nairn’s critique of the drab illiterate-built environment of England and later Reyner Banham’s article ‘The new Brutalism”. The Greater London Council (GLC) and each local council in London had its own Architectural and Planning departments; all eagerly embracing these writings in their creation of a new London. The GLC film on Thamesmead captures that confidence perfectly. The buildings were bold and the forms striking and each borough, as captured in this book, has examples, some more than others.

A building is as much a product (if not more) of the commissioning client’s desires and aspirations as the designing architect’s hand. Councils all over the land with Owen Luder (twice president of the RIBA) and their departments on hand rebuilt many a civic centre. The Council architectural departments, once the major employer of architectural graduates, also had a steady stream of work. As Phipps describes in the Forward, it is increasingly difficult to locate and identify these now much maligned works. Vilification, both of the act and the resultant object, has replaced many with more anodyne constructions or just desecrated their bare concrete, as found materials honesty with a coat of Magnolia Thatcher paint.

If one maps out all the buildings photographed in the book, it becomes apparent that the two excellent walking routes around London; The London Loop and the Capital Ring run in green circles outside and inside the clusters of surviving buildings. Greenwich is missed out which given that Newham is included does not quite seem logical. A previous collection, “Brutal London” covers the central boroughs.

Phipps does not discuss the Brutalist historical term and sensibly throws in a few recent examples of the Smithson legacy which demonstrate that design can produce better solutions than the anodyne suburban tower clusters that we are now being treated to and which Mr Nairn would have a word or two about. The book awakens a curiosity in the subject in a most satisfying way by celebrating and cataloguing an oft-derided and omnipresent architectural style.