Post

Event Report | London's Forgotten Disasters

26 May 2022

Matt Brown, editor at large of The Londonist and author of books such as Everything You Know about London is Wrong and The Atlas of Imagined Places held another London Society audience captivated with tales from the capital's past. Josh Fenton reports.

When we think of disasters, plagues, explosions and ‘great’ fires come to mind, but Matt Brown wanted to show us incidents that may have dropped out of common knowledge, like lightning strikes and airfield collisions. Having investigated some of these lesser-known disasters Matt sought to present a high-level understanding of each and demonstrate why they were as important then as now.

The Battersea Roller-coaster disaster which saw 5 people killed was a very recent event, occurring in 1972. Yet only a few of the audience had heard of it. The mind boggles to think that such safety lapses are still happening today, though the costs for contemporary proprietors are much greater.

Scrolling back to more distant times, Matt shared a patchwork understanding of what might have happened on a fateful day in the 13th Century. A fire broke out near Borough Market and quickly spread to London Bridge. St Mary Overy Church (the modern day Southwark Cathedral) was destroyed, and the plumes of smoke brought many both to help and to gawp. Unfortunately, a draught of wind blew embers into the air, setting both sides of the bridge on fire. Hundreds of people were trapped, some dying due to exposure to the fire, and others jumping into the river. There are no accurate records from that time, but it could be that as many as 3000 died that day.

Similarly instantaneous were the Moorgate Foundry explosion of 1716 in which 17 died and the ‘The Fatal Vespers’ of 1623. Forced into practising their religion secretly by the restriction of Roman Catholicism, a group of Catholics were meeting at Hunsdon House in Blackfriars when the floor gave way. It's thought that as many as 100 people died.

Around the early 19th century people involved in building and industry began to look for ways to prevent disasters from occurring, especially given the human and economic costs. In 1867, the ice skaters in Regent's Park found themselves in peril when the ice broke through. Heavy garments weighed down many of the skaters and others were simply caught in the rush to escape. 20 years later, after the lake had been built up with rock and sand, a similar death toll was prevented.

The Great Beer Flood of 1814 may sound comical, but it was quite costly. At least eight people, including young children, were killed when a 7ft vat of beer in the Meux Brewery in Tottenham Court Road was overfilled and burst into the streets. In 1878 the greatest single loss of life to befall London (at least in peacetime) occurred when a paddle steamer, The Princess Alice, full to capacity, collided with a colliery ship transporting goods. Between 600 and 700 people died.

Looking back to land, Matt shared the story of the Colney Hatch Asylum fire which spread aggressively when one of the women's rooms caught fire in the Jewish wing. Though the building was grand, there was poor fire provision and 52 of the patients died. The combination of antisemitism and a sense that the mentally ill were of little value to society meant that little attention was given to the case; it was old news before the embers had settled.

Denmark Street in Soho was the scene of another catastrophic fire in 1980, when a man was turned away from an illegal nightclub because he was too drunk and returned with a can of petrol which he poured through the letterbox and set alight. The force of the flames and the speed at which they travelled meant that some of the 37 victims were found still sat at their tables.

More recently still, in 1994, a pornographic cinema near the very building in which our event was hosted was set ablaze. A man got into an argument with the doorman, and he too returned with a petrol can and set the place alight, and there were 11 fatalities.

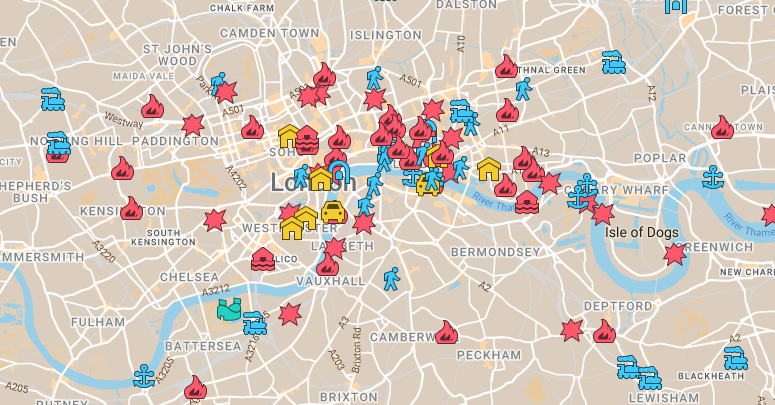

For the latter part of the evening, Matt shared the overlay maps he'd been developing for the last 10 years. These showed a variety of incidents, tube disasters, bombings (including V2 strikes), explosions, and human crushes. One of the audience had a very close relationship with one of the bombings annotated on the map because his mother frequently recounted the story of the bombing of Barnsbury Pub. By chance, she had just finished bathing her new-born son at the moment of impact and a cloud of soot descended from the chimney onto the child. The maps marked moments which were easily overlooked, like the site of the first bombardment attack in 1000 years and ones where clear incisions were left in the earth.

After such a talk it would have been expected that the audience was stunned into silence, but they were full of observations and comments. One of the audience had a distant relative on board the Princess Alice. He thought how much of a moment it would have been for London given how universal pleasure cruises were at that time.

Others wanted to know whether some of the forgotten incidents were wilfully overlooked? Matt thought that probably was the case for many of the disasters discussed. These disasters involved people who were not high in public regard; immigrants, LGBTQ+ and Jewish communities. There was often an attitude of "forget it and move on!"

One of the audience also wanted to ask about how archivists and journalists played a role in helping us to forget such important moments of history. There is responsibility across the board according to Matt. On the one hand, we note that early journalism only had two aims, primarily to compliment advertisement space and secondly to record the political and infrastructural ramifications of disasters and damage. Human tragedies were therefore low on the priority list. When sensationalism crept in in the late 19th century this meant there was increasingly a focus on stories that would sell. Inevitably that meant stories about 'undesirables' were left out, or if covered there was an unashamed tone of derision and condescension.

One of the best ideas of the evening was that in 10 years time it will be harder for us to forget, we are all journalists now with our camera phones ever at the ready. If that had been the case during the times of IRA attacks in London, who could have forgotten the train driver shot dead for thwarting one of their plots. The graphic and visceral Horror of it would never be forgotten he mused. The only question Matt asked was how will we actually collect and gather in all the material stored on the countless millions of devices?

Matt's talk was streamed live via The London Society Facebook page, and we shall attempt to do more of our talks this year in this 'hybrid' format (live events, but with recordings available afterwards).